Allegation One: That the malarial mosquito is unquestionably one of the greatest enemies of mankind

[back]

IMPORTANCE OF MALARIATo estimate the loss attributable to malaria throughout the world is impossible of anything approaching accuracy. The most distinguished observers and scientists of Italy sum up the situation in that country with the statement that "Malaria costs Italy annually untold treasure." Leslie, an English investigator, estimates the mortality in India from this cause at 1,030,000 persons annually in what is termed "an ordinary malarial year." Dr. Ross, the great scientific luminary, has estimated that in the population of Greece, amounting to 2,500,000 inhabitants, there are 900,000 cases of malaria; and he attributes the degeneracy of that great race of people to their being so generally afflicted with malaria. Scientific men estimate the loss from malaria in this glorious country of ours at $250,000,000 annually; and this estimate is said to be very conservative.

Our own Dr. W. A. Davis, the able Secretary of the Texas State Board of Health, in a report to that Board, has estimated the loss from malaria in his state alone at millions of dollars. The same area of territory as that requisite to grow the North American cotton crop, some 79,000,000 acres, which are as fertile as the delta of the Nile, lie dormant and uninhabitable on account of mosquitoes and malaria.

We import two million ounces of quinine for home consumption annually, in addition to the 2,500,000 ounces which we make ourselves. It would be very conservative to state that there are 20,000,000 bottles of "chill medicine" in one form or another consumed in the United States every year. Every druggist makes his own favorite chill medicine, or has it made for him; and there is hardly a little country store that has not a small stock of anti-malarial medication.

Malaria, ague, chills-and-fever, dumb chills, intermittent fever, are the common names of this very-wide-spread disease. The word "malaria," which means bad air, was given to this sickness by an Italian writer in 1753. It was supposed to be contracted by inhaling the thick, damp air common around swamps and lowlands. It has been suggested that the name "mosquito fever" be adopted; a position well taken, when we consider the complete knowledge we have of the disease at the present day.

The literature on malaria is enormous. Several thousand books and articles have been written; but, with the exception of one, all deal with the transmission of the disease to man, and from man back to the mosquito, etc. As far as the writer has been able to ascertain, only one book has appeared on the influence of malaria upon history, though eighty years ago, MacCulloch, a brilliant English observer, complained of the great indifference displayed by Englishmen to the damage caused by that scourge. The disease was known one thousand years B. C.; but it was only in the year 1880 that a distinguished Frenchman, Lavaran, discovered the parasite.

Columns could be written on the effect of this disease upon the different people of antiquity since its earliest recognition ; and their methods of its treatment ranged from tortoise blood, alligator dung, and crushed spiders, to religion, magic, and charms. With such therapeutic agents in combating a disease, the origin of which was entirely unknown to the ancient world, it is no wonder that the rise and fall of nations can be attributed to it; nor are the popularity of the dream-oracle, the belief in charms, and the superstitions of the cultured classes to be wondered at, when without the proper remedies, or the understanding of them, malaria was on the increase.

The most illustrious sufferer in the long ago is mentioned by Ramsey in his book, "The Church in the Roman Empire," page 64, in which he holds that St. Paul was a victim of malaria, and the disease is referred to as the "thorn in the flesh."

Malaria is caused by a greater or less multitude of animal parasites which penetrate and occupy the red corpuscles of their human host, destroying those they occupy, and producing an anemia, or poverty of blood, and other disorders. In some cases the parasite may remain in the body for years with no manifestation of fever to warn its host of its presence, though it is continually undermining his health. The disease is transmitted by certain mosquitoes belonging to the genus Anopheles, and can be contracted in no other way.

Most of the diseases with which the layman is acquainted are bacterial, which means that they are produced by bacteria. The terms bacteria, germs, microbes, microorganism, are all synonymous. The bacteria are defined as "the lowest of all organized forms of life." Typhoid fever, measles, scarlet fever, smallpox, whooping cough, etc., are bacterial diseases; and most of them, as a rule, attack but once, and, by a very complicated process, confer an immunity.

The causative agent of malaria does not come within the definition of the bacteria, as it belongs higher up in the type of life, being classified as a protozoan. This is defined as "A collective term for the lowest members of the animal kingdom, distinguished by their simplicity of structure, etc."

As we speak by comparison in order better to convey or enforce our thoughts, let us make a comparison for the blood-stream coursing through our bodies, nourishing all the different organs. If we had a large moving trough, at which all kinds of animals waited to be fed, we, of course, would have to provide and place therein the different foods suitable to the different species of creatures. The lion would not care for the hay—he would wait until the meat got around; the dog would refuse the corn, but the horse would not; the cat would not eat the nuts, but the squirrel would, and so on. Imagine what complexity of material the blood must have when it has to nourish the liver with what it needs, the heart with what it needs, and so on; and that blood to contain an animal parasite feeding on it, which, being a living thing, performs physiological functions, necessitates that its effete products are thrown into the blood, and that the different organs and tissues must be nourished on that poisoned blood. In addition to this, as was stated previously, "the parasite penetrates and occupies the red corpuscles of the human host, destroying those it occupies and producing an anemia." The individual infected with malaria soon acquires a constitutional perversion of nutrition, which is known as the malarial cachexia. The word cachexia is very commonly used in the Spanish language to denote a person in a run-down condition, characterized by a muddy or sallow complexion, or of a general unhealthy appearance. As we shall have occasion to use the word quite frequently in this Allegation, the reader will kindly keep it in mind.

As has been said, the malarial parasite selects the red corpuscle as its normal habitat, but it does not merely occupy the corpuscle—it gets its nourishment from its contents, and when these are exhausted, it ruptures the corpuscle, and immediately enters another, and another, and so on, destroying each as it leaves. This corpuscular destruction soon begins to leave its imprint on the body, and the infected person acquires a poverty of blood which, as said before, receives the technical name of anemia.

Now, it is this condition that brings about the malarial cachexia. A person with this perversion of nutrition has hanging over him a veritable sword of Damocles, as his body-resistance is so greatly reduced that he becomes very susceptible to any of the important bacterial diseases. If such a person acquire typhoid fever, pneumonia, or some other microbic disease, he is, indeed, in a very serious condition; for he has been infected with another very powerful devitalizing agent, and now has two to contend against.

This does not mean that a person infected with malaria and its cachexia has an aversion for food, but that he is run down, has usually an earthy sallowness of the skin, and a generally unhealthy appearance, particularly when compared with a person of strong, rosy, robust constitution. In the body of such an ailing person the activity of the trillions of minute cells, of which the said body is composed, is at a low ebb. Those wonderful natural phenomena by which all the tissues of the body are nourished are sluggish in allowing nutritive material to pass in and out of the cells. Consequently we are confronted with a low grade of nutrition; and the malarial subject, though not necessarily ill, suffers not from a lack of harmonious action on the part of the body-cells, but from a low pitch of that harmony, or from lack of tone. All of this is due to the enormous destruction of the red corpuscles and because of the toxins thrown off and other damage done by the malarial parasite. It is comparatively easy, even for a layman, to distinguish that particular condition in regions notoriously malarial. But in communities not notoriously, malarial, the disease is not recognized as such, perhaps on account of the prevailing belief that there is no malaria in that community.

The malarial cachexia, or that particular constitutional perversion of nutrition which accompanies the chronic form, manifests itself in hundreds of ways. For instance, the infected person may experience today no ache or pain,—in fact, as he might say, "never felt better." Tomorrow he may feel so bad that he must drive himself to his work. Perhaps he awakens in the morning apparently perfectly well, though during the day he may have a yawning spell, or have cold shivers running down his back. He may become nervous to the extent of neglecting his work, or of snapping at his best friend, or he may get a bad case of the "blues." If inclined to take an "occasional" drink, at this particular time he might take two or three, which will restore his feeling to the false normal. The alcoholic stimulation tends to overcome the depression due to the fact that the parasites were at that time sporolating (which means breeding or hatching) and pouring into the blood-stream millions of their own kind with the concomitant debris.

In women with this infection the nervous manifestations are much varied; displays of temper and depression, physical as well as mental, are very common; these spells, however, may not be characteristic of the woman, but are symptoms of malarial poisoning, and are entirely concomitant with the cycle of evolution of the parasite. Perhaps, the day following, the feelings and conduct of this same woman will be so radically different from those of the day before that she might be referred to as "the sweetest thing on earth." Of course, weeping is a necessary accompaniment.

Women who have everything in life to live for, in fact, "in life's green spring," very often, though unconsciously, cause little ripples of discontent to flow into their homes by exhibitions of the "blues," which perhaps may lead to waves of discordancy. As the malarial manifestation usually follows the multiple of seven, depending on the type, at certain times she might attribute her depression or ill feeling to the approach or establishment of the normal physiological function peculiar to her sex, which, in fact, has no more to do with her ill feeling than have the reflected rays of the moon.

If her malarial manifestation is in the form of a sick headache, or facial neuralgia, she resorts for relief to the different "ines," antipyrine, exalgine, antifebrine, 'etc. She adds fuel to the fire by attacking the symptoms of a cause with poisons which strike directly at the red corpuscles, already badly crippled by the malarial parasite. If she should be so unfortunate as to find relief in that most seductive of drugs, morphine, it is only a question of time when she becomes an habitue; and then self-respect, family, home, friends, and everything held dear are thrown to the winds.

As it is popularly believed that malaria is necessarily accompanied by fever, it should be impressed on the laity that fever is not a necessary antecedent or accompaniment of chronic malaria or its cachexia. In notoriously malarial regions it is by no means unusual to see typical examples of this condition in which fever never has been a feature, or is of a mild character, or had occurred in childhood and had been forgotten. The subject of this cachexia can go on for an indefinite period without any manifestations until he experiences a severe exposure or fatigue, or until some profound emotion or physiological strain occurs, when the parasite is again fanned into activity.

To mention some of the most common symptoms of the malarial cachexia, it might be said that, in the growing child, its development, both mental and physical, is delayed, and the general growth of the body is stunted. Neuralgia, stomach disorders, vomiting, diarrhoea, headaches, attacks of palpitation, sneezing, general lassitude, the spitting of blood, nose bleeding, and retinal hemorrhage are not infrequent. The malarial subject is apt to be dyseptic; to suffer from irregularities of the bowels, or from diarrhoea. On account of long-standing congestion, associated with anemia, the blood-making organs become diseased; and then, in spite of the removal of the malarial influences, the trouble inevitably progresses to a fatal issue.

The large amount of toxins thrown off by the parasite, with the countless millions of destroyed red corpuscles which the phagocytes carry for elimination to the alimentary canal, cause the infected individual to feel "achy" or generally bad, when he proceeds to the making of his own diagnosis, by charging himself with being "bilious," a term as vague as it is popular.

In the acute form of malaria the diagnosis is indeed a matter of no difficulty at all, but in the chronic form, and with its cachexia, it is quite a different matter. The microscope is a most unsatisfactory instrument to depend upon. Often the infected individual is assured of his non-infection by a microscopic examination of his blood, when he may have numbers of colonies ensconced in his system. The damage done by such a wrong diagnosis is self-evident. This noble instrument, however, does reveal another of Nature's secrets, and so furnishes protection from the malarial parasite.

If we examine microscopically the blood of an individual infected with an acute case of malaria, we shall have no difficulty in finding the parasites; but, after administering only one dose of any of the anti-malarial remedies, such as quinine, cinchonidia, or any derivative of the Peruvian bark, they leave the circulation, and no amount of the most assiduous work on the part of the most expert microscopist could find a single one. Have they been killed out by the quinine or cinchonidia? By no means. They disappear from the blood stream until the remedies applied have been eliminated, when they return and can be easily found.

A radical change of climate or a long sea voyage will cause this ensconcing, with, of course, a bettered condition of health following. When, however, the individual returns to his usual avocations and duties which call for mental and physical energy, he relapses into his old condition, because the parasites have found their way back into his bloodstream, in order to reproduce; and again they establish their cycle of evolution—all of which can be easily demonstrated by the microscope.

A sojourn at a mineral spring or health resort will sometimes cause the ensconcing, as the individual usually goes to such a place for the express purpose of resting, and leaves all care behind. The purgative or laxative effect of the water, with perhaps the large quantities drunk on account of the high reputation of its curative value, simply flush his entire system and rid it of products that have already served their purpose in the body and are pent up. This sojourn betters his condition by making him more resistant to germ and parasitic influences. Old Dame Nature knows this, and, therefore, to protect the malarial parasite, she causes it to hide away.

If the microscope does not show the parasite in any of its different forms, then, of course, the diagnosis becomes positive. The diagnosis is difficult in the so-called "latent stage," which is a predominating factor for the perpetuation of the disease.

The newspapers and popular magazines have rendered a great service in diffusing the knowledge that mosquitoes transmit malaria, but they have in the past very much neglected MAN as a focus of infection.

A distinguished writer says: "It is a common occurrence to find the parasite in the blood of patients. These patients are malarial carriers, who perpetuate the disease in those sections where meteorological conditions are such as to destroy the parasite in the mosquito during the winter months, and are a most serious factor in any community considering a campaign against this disease. Malarial carriers are absolutely responsible for the perpetuation of the disease in temperate climates, where the mosquito becomes free from infection during the winter months. The latent carrier also largely enters into the dissemination of the disorder even in tropical countries; and it cannot be emphasized too strongly that the destruction of the parasites in these carriers is equally as important as the destruction of the mosquito."

While this would be most desirable, it can be seen at a glance how impractical of application this is, since in some communities from 50 to 100 per cent of the inhabitants are infected, and as no one would consent to take a long course of anti-malarial medication, particularly when he "appears to be suffering no inconvenience as a result of harboring the parasites."

While we know positively that the nocturnal variety of mosquitoes termed anophelines convey malaria, we are not positive that other varieties do not convey it, so that the geographical range of malaria can be placed on this hemisphere as extending from Alaska to Patagonia.

UNIVERSAL OCCURRENCE AND POPULAR TREATMENT OF MALARIA

It is a mistake for some communities to assume that they have no malaria among them; because the reports from the medical profession to the health officer are necessarily incomplete, for the reason that the disease, chills and fever or malaria, on account of being so well known, is self-diagnosed and largely self-treated. This is due to well-directed advertising on the part of the patent medicine industry, the familiarity of the laity with the disease, and the apparent and supposed cures these medicines effect. Surely a person who has stopped his chills with a bottle of such medication, and has thereby saved a doctor's bill, remains a firm believer in its efficacy. He little knows that he is converting his acute case into a chronic one with its accompanying cachexia, and himself into a carrier.

The best evidence of the great prevalence among the laity of this self-practice in malaria is the fact that there are sold in the United States annually, not hundreds, nor thousands, of such bottles of chill cures, but MILLIONS. In addition to the much advertised and so better-known brands of chill medicine, every druggist makes, or has made for him, his own malarial cure, which really is just as good as the patented article. His own cure, affording a larger profit, is given preference, and is unhesitatingly recommended to his customers as a sure cure for chills-and-fever.

All these medications have the same effect, viz., stopping the chills, but perpetuating the disease. It is this class of carriers that the health authorities never hear about, hence it can be seen at a glance that reliable statistics on malaria in any given community are almost impossible. The medications usually contain some derivative of the Peruvian bark, such as quinine, cinchonidia, etc., some of them rendered tasteless by chemical manipulations, which make them better sellers. A return of the malarial symptoms is sure to bring about the purchase of another bottle, which again stops the chills by causing the ensconcing of the parasites; but in the meantime that person is not only infecting all of the mosquitoes that bite him, perhaps transmitting the disease to his family, but is also most effectively aiding in perpetuating malaria.

Some years ago, the writer addressed letters with stamped envelopes to health officers in many towns and cities in every state in the Union, containing this short questionnaire: "Have you any malaria in your community?" "What is the mortality?" "These questions are asked in the interest of science and medical research." Another letter, addressed to the postmaster of every town or city reporting "No malaria," was sent requesting him kindly to hand the enclosed self-addressed and stamped envelop to the most prominent druggist for reply. These letters contained the following question: "How many bottles of all kinds of chills-and-fever, or malaria, medicines, do you sell in a year ? An approximate number will do. This question is asked purely in the interest of science and medical research.'"

Not a single one of those answering from the same cities and towns in respect to which the health officer declared "No malaria here" confirmed the statement. But they all reported one or more different kinds of chill medicines sold. Hence it can be seen that hardly any community, large or small, can be said to be free from this world-wide disease.

In stamping out any disease, the sources, or foci, of infection must first be found. For instance, in stamping out yellow fever, also a mosquito-borne disease, with its notorious and swift epidemicity, if we are fortunate in discovering the first case, the sufferer is immediately isolated, or, better said, screened with mosquito netting, to keep the mosquitoes from biting him. If this is done for the first few days after the onset of the disease, which manifests itself in no uncertain manner, that case ceases to be a source of infection, as, after a short period of time has elapsed, the mosquitoes that bite that patient will not be infected, and thus a threatened epidemic is nipped in the bud. Should the individual recover from his attack of yellow fever, he not only ceases to be a carrier, but is immune to the disease. This, unfortunately, does not apply to malaria, as the infected individual continues to be indefinitely a carrier.

It is among the poorer classes where we find malaria most prevalent, because they live in small, cheap-rent houses; and, knowing nothing about the danger of mosquitoes, do not bother about screens, or are too poor to buy them. On hot summer nights, they sleep, perhaps, upon a quilt on the front or back gallery, to escape the heat of the room, and, therefore, are more exposed to mosquitoes. The man with a little more of this world's goods than his poorer brother also pays his tribute to malaria when he goes with his family for a short camping trip to the stream or lake nearest his home. He usually leaves on Saturday afternoon, spending that night and the next day in the woods, returning Sunday night, in order to resume his duties the next morning. Little does this man count on the indirect cost of the camping trip, when he is exposing himself at his trot and set-lines, and when his family is using "mosquito lotions" to be able to sleep. The lotions evaporate about the time the campers are fast asleep, and the mosquitoes bite and inoculate without hindrance from volatile oils, or from being slapped at.

The rich man, like his poorer brothers, also pays his tribute to malaria when he takes his family during the summer for a camping trip, or a long overland journey, leisurely made by camping and fishing along the mountain streams en route. This man carefully plans his trip, and omits nothing, except mosquito bars, that might add to the pleasure and comfort of his family. These bars would afford protection to some of his family, but not to those of them fond of fishing at night; and the fisherman insures his infection by carrying a lantern, which attracts mosquitoes to him. With the advent of winter, some of the family become ill of malaria; he wonders how that is possible, and refers with pride to the fact that his home is screened and mosquito-proof from cellar to garret.

It has come under the author's professional observation that, as good roads are being opened up, the automobile is becoming more and more a most powerful ally of malaria. Time and distance have been annihilated by this great invention, so that the favorite bathing place, camping ground, or fishing resort is at best a matter of but a few hours from the crowded city. The more beautiful and inviting the place, the more certain it is to be sought after, particularly if some near-by farm is handy to furnish the indispensable eggs, milk, etc.

Would the reader go to such a place with family and friends for an outing, if he knew that smallpox had broken out among the people camping there last? Unthinkable! Yet some of those camping there last were malarial carriers and infected the mosquitoes; and, sufficient time having elapsed for the cycle of evolution to complete itself in the body of the mosquito, the disease, malaria, can be contracted by your family and friends with much greater certainty than the smallpox would have been transmitted.

The trans-country, automobile tourist going leisurely through the country, on reaching such a beautiful, shaded place with the banks of the limpid stream freed by previous campers from weeds and underbrush, concludes he has found the ideal location for a long rest in order to clean up, make necessary repairs to his machine, etc.,—in fact, for a while he doesn't wish to go any farther. Little does he realize that he or some of his family will soon be carriers of malaria, and, if they remain at that beautiful place long enough, will indirectly infect others who come there after their departure, thereby unconsciously aiding and abetting Nature in the enforcement of her inexorable laws.

Owing to the new order of things coming very much into vogue, the camping automobilist need not in the least worry about where he is going to camp or how desirable the place will be at his next stop, as camp-sites are being provided by different municipalities which are ideal for just this purpose—all of this being made possible by the automobile.

These sites are arranged along the shaded banks of beautiful streams, which are not only cleared of all weeds and rubbish, but are made more inviting by providing fire places, tables, benches, etc., for the comfort of the campers.

In quite a number of instances, screened and floored tents, or neat little cottages nicely furnished are to be found on the banks of the crystalline stream, so that the camper can save himself the annoyance of over-loading his machine with camping accoutrements. Here the camper finds the acme of outdoor life—back to Nature—varying the monotony by visits to the city or town nearby to replenish the larder, to attend church, visit the movies, or see a game of baseball. In fact, he and his family are enjoying their nomadic life with a minimum of inconvenience.

But living "next to Nature," becoming her guest, as it were, means to accept the Old Lady as she is, and not as we would like her to be; so the campers must unwillingly mingle with her other creatures, the most undesirable of these being the malarial mosquitoes. The campers cannot escape these insects, as they are the natural denizens of the watered rural districts; and they transmit to the new comers the malaria which they acquired from the previous campers. In so doing they are simply obeying the inexorable laws of their Creator, who has seen fit to construct their baneful little bodies for just this purpose—the perpetuation of another form of life.

From this it would seem that, if we must obey our primitive instincts to enjoy ourselves, and in our "love of Nature, hold communion with her visible forms," and "go forth under the open skies," it would be best to pattern our ideas of "Safety First," from that notoriously crafty and suspicious bird, the crow, in the fable so well known in Latin-American countries: "An old crow and a young crow were perched on the uppermost limbs of a dry tree along the roadside, the old crow with his head in one direction, the young crow with his head in the opposite direction. The young crow, seeing a pedestrian coming in their direction, but quite some distance away, said to the old crow: 'There is a man coming up the road toward us; and if I see him stoop, we'll fly away.' The old crow without as much as turning around to see, said: 'No, we'll fly now, he might have a rock in his hand.' "

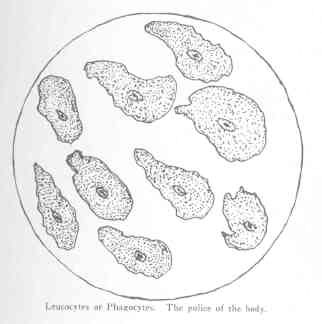

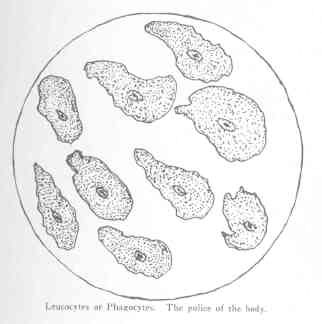

Figure 1 is a drawing of the white corpuscles, leucocytes, or phagocytes. They are the real defenders of the body, and are found in the blood in about the proportion of one phagocyte to seven hundred and fifty red corpuscles. Their functions could be likened unto those of the police force of a city, as they wander aimlessly about in the circulation until called for duty.

For instance, say one receives a cut or a wound of any kind. Information of such injury is immediately imparted to the brain, and the phagocytes in large numbers find their way to the wound, which they surround in columns with almost military precision, ready to attack whatever bacteria might have been on the implement that produced the breach of continuity, or on the skin and introduced into the wound. ' They throw out one, two, or three finger-like projections; and the bacteria stick to the phagocytes like flies to sticky fly-paper. It may be, however, that the bacteria are of such a poisonous nature that they kill the phagocyte, but that is of little moment, as there are columns after columns behind one another, so that if those at the immediate front succumb, the next column takes their place, and so on until the bacteria are destroyed.

Leucosytes or Phagoctes. The police of the body.

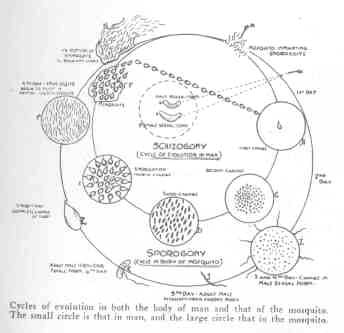

Cycles of evolution in both the body of man and that of the mosquito. The small circle is that in man, and the large circle that in the mosquito.

Now, very much like after a fight between our peace officers and a number of bad men, the dead on both sides must be removed, so when we look at a wound and see it festering, the matter which we perceive is largely the dead bodies of the phagocytes and the invading bacteria, the latter having been killed by the former, who in turn also died like valiant soldiers in line of duty. Of course, the wound should now be opened, or it will open of its own accord,and soon rid itself of harmful material. Columns of phagocytes will still be on guard in the surrounding healthy tissue until the wound heals, and until their services are no longer required, when they will again return to and wander aimlessly about in the blood-stream, awaiting another call.

However, it sometimes happens that the phagocytes lose the fight and the invading bacteria are victorious and not held within the small area of the wound, but enter the blood-stream and cause the familiar condition known as blood-poisoning. Such instances occur in the bodies of people who are "run down," or in general bad health, due to disease, debauchery, or poverty. In these cases the defending phagocytes are weakened, smaller, and much lessened in number from the normal; therefore they do not have the defending or fighting qualities Nature intended them to possess ; and the invaders, not being arrested, overwhelm the body.

In malaria there is a constant battle going on between the phagocyte and the malarial parasite, but the phagocyte is very much at a disadvantage, in that it can attack the parasite only after it has ruptured the corpuscle (see Figure E); and countless millions of the parasites are thrown into the blood-stream, until each parasite again penetrates a corpuscle to continue the cycle of schizogony. After it has penetrated the corpuscle, the parasite is perfectly safe, as the phagocyte will not tear the corpuscle to reach it.

From this we perceive that Nature, who has given us this wonderful avenue for protection from these minute, invisible, but relentless foes, the bacteria, actually limits the protection of this particular parasite and allows it to thrive in the red corpuscle of man, which she intended to be its normal habitat. Astounding? Yes, but this assertion is

made advisedly; just as much as the Polar regions are the home of the Polar bear, or a cave in the wilderness is the home of the wolf or bat, or a hollow tree is the home of the squirrel, just that much is the red corpuscle of man the normal habitat of the malarial parasite; and, as said in the preface of this book, it is man and his kind only that carry this parasite. None of the domestic or wild animals carry it; it is distinctly parasitic to man. Cruel, the reader would think? Yes, but he must consider that there is no such thing as emotion associated with the works or so-called "mysteries" of Nature.

As a striking example of the cruelty and kindness, as we would view it, of Old Dame Nature, permit me to cite you the case of that large species of the spider family known as the tarantula. An insignificant little wasp pierces with its sting the motor centers of the spider, and completely paralyzes it, as far as motion is concerned. After it has overcome its struggles following the sting, it remains perfectly quiet, afflicted by locomotor ataxia, as in man. It is then that the wasp pierces its large abdomen and lays its eggs, which in the course of time develop into the larvae and adult wasps. If the wasp, by its sting, should destroy both the motor and sensory centers, it would kill the tarantula, and the hot sun would soon dry it up, so that it would not afford food for the baby wasps. What guides the delicate little lance to the motor centers of the tarantula? Here we see extreme cruelty in the tarantula being slowly consumed alive for the perpetuation of another form of life, and extreme kindness in providing such a magnificent abode and abundance of food for the baby wasps.

Thousands upon thousands of cases of tuberculosis are cured by Nature, as is evidenced by post-mortem examinations. Thousands upon thousands of cases of pneumonia, typhoid fever, scarlet fever, measles, smallpox, and other microbic diseases are cured without the slightest medical intervention. Nature cures them. Does she cure malaria? The answer calls for another question. Does Nature defeat her own schemes? Is there any reason why Nature should favor us? Our bodies belong to Nature, our souls belong to God.

As we are discussing in a cold, dispassionate manner one of Nature's lowliest of beings and its most intimate association with her greatest of architectural triumphs, let us leave the works of the master minds, swivel chair, roll-top desk, and microscope, and again "go forth under the open skies," and we shall witness a striking analogue of parasitism in the vegetable kingdom.

A little plant, the familiar mistletoe, played a conspicuous part in mythology among the Norsemen and the Druids, for whom it had not only curative but also magical powers, attributes still surviving in modified form in our Yuletide custom of kissing under the mistletoe.

Doubtless there are other parasitic plants that play the same role as does the mistletoe and present identical analogies; but the mistletoe is so familiar and can be observed with so much ease, that we shall use that parasitic plant for our analogy.

The mistletoe does not thrive on all trees, any more than the malarial parasite thrives on all mammals; some trees seem to be immune to the parasitic mistletoe, just as all creatures in the animal kingdom, except man, are immune to the malarial parasite.

Let us select some particular specimen of the deciduous trees which is infected by this vegetable parasite, choosing, say, a hackberry tree for observation. The tree may have two or three clusters of mistletoe, which are readily visible in autumn and winter on account of the absence of leaves. Year after year the clusters will increase until it has quite a number; but, judging from the green leaves, little flowers, and berries which it brings forth in such profusion, and from the beautiful shade it affords, year in and year out, like the Master of the Animal Kingdom infected with malaria, it "appears to suffer no inconvience from harboring the parasite."

If we continue the observation over a period of years, we shall see at first a few of the uppermost limbs begin to wither, indicating a lost resistance. Like its deristant, infected human contemporary who becomes a prey to any of the disease-producing bacteria on account of such lowered resistance, due to the biological activities of the malarial parasite, the trunk of the tree soon affords the proper environment for the existence and multiplication of boring insects; and the parasitic mistletoe is gradually starved to death by its expiring host, for whose untimely destruction it is the direct cause.

As the malarial parasite has its normal habitat in the human red corpuscle and finds therein its nourishment, so the mistletoe resides on the hackberry, but it does not penetrate the woody part of the tree. When the seed finds lodgment, it spreads its growth into the bark only; and, although its texture is radically different from that of the bark of the tree, it merges its own bark into that of its host.

So perfect Is this natural grafting that the lines of demarcation are almost obliterated by the growth. In fact it becomes a part of the tree, and derives its nourishment from it, just as do any of its own limbs or branches. But the part it plays never allows the tree to reach such a ripe old age as to permit it to be called a "Monarch of the Arboreal World."

The author has been observing this parasitic plant for a period of over twenty years, and in all that time has never seen it wither and die—evidently it is very resistant to disease. A dead cluster, however, is sometimes observed, but this condition has been occasioned by its being mechanically injured in a storm, or by a bird nesting in its clusters.

One of the high-class magazines sometime ago contained a description of brilliant experiments on plant life by a European scientist, who sought to demonstrate that plants had all manner of feeling, in fact, nerves. Should this prove true, what an added amount of suffering Nature has inflicted on the mundane life which she governs with such a ruthless hand! If the tree could speak, would it not cry out to the weary traveller who seeks shelter under its cooling shade from the sun's fiery rays? Would it not appeal to its feathered contemporaries who seek its branches for a trysting place, and so lovingly and laboriously make a home for the dear little hearts to come, to rid it of this merciless barbarian ?

And even Aeolus, as if to pity it for its fate, sends the sweetest of its messengers, the gentle summer zephyrs, which, as they pass by, convert the delicate withered branches of its crest into an aeolian harp, the harmony of which sounds one continual dirge, constantly reminding it of that majestic force, Nature—the force of all forces from which nothing can be expected that might have the slightest semblance of pity, tenderness, or mercy, and which knows nothing of these gentle virtues.

Another striking analogue of malaria in the human is seen in a parasite which finds its normal habitat in the red corpuscles of cattle, and causes a disease known to the cattle industry as the "tick fever," and sometimes as "malaria in cattle." This will be dwelt upon hereinafter when treating concerning the "Functions of the Spleen."

A person bitten by an infected mosquito today is infected; if bitten 25 or 30 years ago, that person has been infected and a carrier that long, at times exhibiting very obscure manifestations of the cycle of evolution, which he attributes to any but the correct cause.

As the general trend of opinion seems to be that all real knowledge must have a European origin, I quote Mons. Jules Carles, the eminent practitioner of Bordeaux, on the "Treatment of Malaria":—"insists that malaria belongs in the same class with syphilis—as a disease eminently chronic, with frequent revivals of manifestations and requiring treatment over years as with syphilis." The reader will note that this eminent physician does not give it as his opinion, but "insists' on his conviction as to the seriousness of malaria. This eminent gentleman's insistence on the seriousness of that disease requires no endorsement, but the author is perhaps a little better qualified to add high approval than the average practitioner, as for years he has been limiting his practice entirely to two diseases, viz., malaria and typhoid fever—the former on account of its importance and extreme difficulty of eradication, and the latter because of malaria constituting with it a most formidable complication.

In the treatment of disease, the more the educated physician caters to old Dame Nature, the more certain is his reward in curing his patients; but in malaria he has a physio-pathological condition to deal with, as he is endeavoring to expel one of her own creatures from the home she intended it to occupy.

It is the most ardent wish of the author that the information contained in this FIRST ALLEGATION will find its way to the Commissioners or Executives of the Councils of the Boy Scouts of America, as he feels certain that they would be more than glad to have it, if they but knew of its import and existence. It is these good men who give their time, money, and service to the betterment of the embryonic manhood of our nation; it is they who not only make manly little men out of ordinary boys and eradicate the "sissy" from the pampered ones, but also inculcate in them ideas

that will make of them future citizens of such quality as will insure the perpetuation of this glorious Nation. But the most essential quality to good citizenship is health; and taking the boys out on a hike to camp on the banks of some creek or mountain stream with no protection against mosquitoes, means the impairing of the highest and best directed efforts of these good men, by undermining the health of their cherished wards.

In 1905, the Greek Anti-Malarial League, a society composed of prominent physicians and laymen of Athens, Greece, came into being; and they have performed a stupendous work in the interest of their countrymen. As a demonstration of the colossal damage sustained by malaria, the society quotes thus the conclusion of certain highly-trained, scientific men who are giving most valuable time to their particular disease:

"The evil consequences are seen in the following ways:

(a) The most malarious districts also are the most fertile.

(b) The loss of time and money is very great.

(c) The effect upon the rising generation is most disastrous.

(d) The victims of malarial cachexia are weakened in body and mind.

(e) The inhabitants of malarious districts age rapidly and die prematurely."

The "Society for Improving the Condition of the Poor," having headquarters in New York City, says that illness causes 96 per cent of cases of poverty, and that only 4 per cent are due to drunkenness, old age, and non-employment. How much of this 96 per cent can be attributed to this world-wide disease?

It has been said that, "Public Health is purchasable," and this is indeed true, but the purveyors and purchasers of that "commodity" can drive good bargains only by directing their activities along self-illuminated avenues, and this self-illumination is KNOWLEDGE.

DESCRIBING SCHIZOGONY AND SPOROGONY

In studying any branch of science we are bound to learn words applicable to that branch, some of which are quite out of the ordinary; consequently, in studying the transmission of malaria, it is very desirable that we familiarize ourselves with the technical terms employed.

As man is as much a factor as the mosquito in perpetuating malaria, let us understand the role they both play. For the continuance of that parasitic form of life, we know that the parasites alternately occupy man and the mosquito. They are continuously undergoing a cycle of evolution or metamorphosis, something on the order of the cycle of evolution of the butterfly from the egg to the cocoon, though infinitely more complex. The cycle of evolution occurring in the body of man, is termed Schizogony, (see Figure 2, small circle) and the cycle of evolution in the body of the mosquito is termed Sporogony (see Figure 2, large circle).

The fine needle-like bodies which the mosquito pours into the circulation of man in the act of biting, are called sporozoits (see Figure A), "Mosquito-implanting sporozoits." The word "sporolating" is equivalent to the word breeding or hatching. The word gammets means the male and female FORMS seen in the small circle on the inside of the large circle describing schizogony and marked H—G. The word, merozoit, is the name of that form of the parasite seen in Figure F.

Figure 2 shows the anatomy of an uninfected normal female mosquito. It might perhaps be well in passing to mention that the male mosquito does not bite; its sole function is that of procreation.

Figure 3 shows the anatomy of an infected mosquito; and the reader's attention is particularly directed to the underscored names of three structures: Ventral food reservoir, salivary gland, and salivary duct. The most important structures for study are the salivary glands, or, as they also might be called, saliva or spit-glands.

See long photo Figure 3. The photograph of the mosquito marked "normal" is a most remarkable piece of ceramic art, and was procured by the author from the owner, the American Museum of Natural History of New York City. The picture marked "infected" is a copy of the same photograph which the author "infected," showing the second-last and final change of the cycle of evolution that takes place in the body of that insect.

There is no more beautiful example of the truism that "Knowledge is Power," than the knowledge of these glands. They are but very little larger than a period made with an ordinary writing pen, yet an intimate knowledge of their functions and behavior made possible the completion of the world's greatest engineering feat, the Panama Canal. When the French attempted the building of the Canal, they had all the requisite equipment: brains, money, and tools,—but they failed on account of not knowing the functions and behavior of the salivary glands.

These glands are given to the mosquito by Nature, principally to harmonize with one of her physical laws. Let us see how. If we had a hypodermic needle made of the length and diameter of a mosquito's proboscis, or stinging apparatus, and if we should attach it to a hypodermic syringe and insert it into the human skin, as does the mosquito with its hypodermic needle, then pull on the piston of the syringe as does the mosquito in the "act of sucking, we would get no blood in the barrel of the syringe; it would coagulate in the needle. Yet the blood in the mosquito's needle does not coagulate. "Why? Because it is a physical property of blood that it will not clot or coagulate in an alkaline medium. For illustration—if we had two glasses half-filled with water, and in the one we dissolved a few grains of any alkaline substance —say, bicarbonate of soda—and in the other were left the plain water, and if we poured some fresh blood into each glass, it would be seen that the blood in the glass with the bicarbonate of soda, or alkaline water, would not coagulate, but that the blood in the glass with the plain water would do so.

Now, the mosquito, in the act of biting, inserts her bloodsucking apparatus into the skin to reach the blood underneath; but, before the process of sucking begins, she injects into the circulation a small complement of alkaline fluid from the salivary gland through the salivary duct, and so alkalinizes the small area of tissue from which she is going to draw blood; and thus her meal is insured by the non-clotting of the blood in that delicate needle, her proboscis.

As can be seen in Figure 4, (long photo Figure 4), "Infected Mosquito," the ventral food-reservoir is filled with the immature sporozoits in tiny globules; and those free in the salivary glands have ruptured the globules and found their way there. It is when the mosquito, in the act of biting, pours the alkaline fluid from the salivary gland through the salivary duct for the purpose already mentioned, that the sporozoits also are injected or implanted in the blood-stream; and then the individual bitten becomes infected, and the cycle of evolution known as schizogony begins.

Figure 2, Schizogony, the cycle of evolution in the body of man, at A shows an infected mosquito implanting the sporozoits. Each small round ring, through which passes the large circle, represents a red corpuscle. After the sporozoit has been injected by the mosquito, it immediately, for protection against the phagocytes, enters the red corpuscle, loses its identity as a needle-like body, and assumes the shape seen in B, C, and D, the second and third changes. At E, the fourth change, the contents of the corpuscle could be likened perhaps unto numerous little olives. This condition is known as the period of sporulation. The corpuscle now ruptures, as seen in F, and countless millions of the parasites known as merozoits are thrown into the blood-stream. Almost immediately, to escape again their enemies, the phagocytes, they re-enter a corpuscle, as in B, the cycle being completed, and are again ready to continue. As far as the individual infected is concerned, the infection can go on no further, but Nature, for the perpetuation of this form of life, evolves certain of the merozoits into the two boat- or bean-like bodies shown in the small circle within the large one, and marked G and H. These bodies are the male and the female forms of the parasite, and are destined for evolution in the body of the mosquito, the smaller, G, being the male, and the larger, H, being the female. These bodies are formed in great numbers after the completion of each cycle, and this takes place every 48 or 72 hours, and can continue for an indefinite number of years. The infected individual is referred to as a "gamete carrier;" and in making a malarial sanitary survey, a community is referred to as being more or less malarial according to the number of "carriers" found.

Figure 2 is a drawing taken from Dr. Graham E. Hen-son's splendid book "MALARIA," published by the C. V. Mosby Co., of St. Louis, Mo., although somewhat modified. The modification consists in showing in circles or rings the various changes on the part of the parasite in the body of man, and is intended to represent the red corpuscle, as all the different changes of phases of evolution occur inside of the said corpuscle. In a foot note explaining the drawing in Dr. Henson's book, he says: "There is no attempt in the foregoing to follow each and every stage of evolution that takes place in the circulation of man, or in the body of a mosquito, it being the aim simply to bring out the salient points that take place in the evolution of the parasite." This applies to the author's modified drawing; and again, to make the different stages of the cycle of evolution that takes place in the body of the mosquito more easily understood, a presumptive approximate age is given to each different phase.

The cycle of sporogony can and does take place only in the body of the mosquito. When the normal or uninfected mosquito bites a man, or better still, a "carrier," she engorges and then rests for a period of time during which she voids the liquid portion of the blood, in order to concentrate her food, digesting all the solid elements except the gametes, H and G. On the first and second day no perceptible change takes place on the part of the gametes, but on the third and fourth days the small gamete, or male form G, enlarges very much (see I in drawing), and throws out from two to eight of what might be likened unto long, thin tails. These detach themselves from the parent body and become the fully developed males (J). About the fifth day they are very active and in quest of the female; and about the sixth day they encounter and fertilize her (H), as seen in K. The female (H) now loses her identity as a bean or boat, evolves into form L on the seventh or eighth day, and is found very active in the muscular walls of the mosquito's Intestine. About the ninth day these bodies begin to evolve into form M, which are the sporozoits; and in another day or two the latter find their way into the ventral food-reservoir. As each little globule, containing hundreds of immature sporozoits, ruptures, the said sporozoits find their way into and become lodged in the salivary glands, to be injected again into the circulation of man, when the mosquito seeks another meal. This cycle requires from TEN to FIFTEEN days, averaging TWELVE, for its completion. If, however, this mosquito should bite a human before the cycle of evolution is complete, she would not infect him, as the cycle is not completed until the sporozoits are in the salivary gland. The reader is kindly asked to keep in mind the time required for this cycle of evolution to complete itself, as it has a very important bearing on the evidence concerning the eradication of malaria.

In comparing the two mosquito pictures, the infected and the non-infected, we see that the mosquito apparently does not mean to be the malignant insect it really is, as its ventral food-reservoir is what its name implies, a reserve or storage for food to be called upon when needed. The salivary glands are to store the alkaline saliva so as to prevent the clotting of its food, the blood, in its delicate, bloodsucking apparatus, the proboscis; and the function of the salivary duct is to conduct the saliva to the blood under the skin. Hundreds of normal malarial mosquitos might bite us, and we would never acquire malaria, even if we lived in a notoriously malarial country.

The work of the demonstration of the two cycles of evolution we have just gone over is regarded as the most masterful piece of medical achievement, and has required for completion twenty-four years of the most painstaking labor on the part of the world's greatest minds.

Nature does not loudly proclaim her achievements or secrets, but she has endowed the highest of her creatures with that God-given function of REASON that he might unravel what appear as her mysteries and use her creatures to his advantage. While it may seem to some of us mysterious and highly perplexing that Nature should choose the body of her greatest architectural triumph, man, and the body of one of her lowliest of creatures, the malarial mosquito, each to take part independently in the evolution of a much lower form of life, she continues the mystery by providing for the destruction of that most malevolent of insects; and, as if to atone to man for the punishment she inflicts upon him, Nature endows her most wonderful creation, the bat, with such habits, and faculties as result in its being one of man's best friends.

This concludes the argument of the "First Allegation;" and it is hoped that there have been advanced such convincing arguments as will warrant the reader in deciding to use not only his personal influence, but also to enlist that of all his friends in spreading this knowledge; because it is only by the diffusion of such knowledge among the school children, our future citizens, and among the masses in general, that we can hope to eradicate the malarial mosquito, which has been shown to be one of the greatest enemies of mankind.

"One half of the world knows not how the other half lives." This hoary axiom might very properly be paraphrased into "One half of the world knows not how much the other half suffers;" and the reader must conclude that a large percentage of that suffering is the tribute Nature demands in the execution and continuance of her schemes. "What a magnificent opportunity awaits the immensely wealthy man who wants to do something really and radically novel and colossally grand in results! If the author could have a personal interview with such a gentleman, he would soon convince him of the fact that the eradication of this malevolent parasite would be the greatest philanthropic work that could possibly be undertaken, because it not only involves our own country, but also the entire world; also that by directing his energies to the one cause, and the one cause only, the greatest of economic problems could be solved, and the creation of a superior nation accomplished, while he himself would be immortalized by handing down to his children and to posterity his fame as one of the world's greatest benefactors.

The preceding dissertation confirms Allegation One.