http://www.life.com/Life/essay/gulfwar/gulf01.html

He gets ear infections constantly, but he never really cries. You know how most children scream when they get earaches? Maybe he's immune to pain." -CONNIE HANSON

When our soldiers risked their lives in the Gulf, they never imagined that their children might suffer the consequences--or that their country would turn its back on them.

Jayce Hanson's birth defects may stem from his father's Gulf War service. But like hundreds of other families, the Hansons face official stonewalling--and a frightening future.

Flying kites with his sister, Amy, he displays a fierce determination. "He's a problem solver," says his father, Paul. Jayce suffers from a syndrome similar to that of the thalidomide babies of the 1950s. But his mother, Connie, took no drugs.

From outside, the evil that has invaded Darrell and Shana Clark's home is invisible. Set on a modest plot in a San Antonio subdivision, equipped with a doghouse and a swimming pool, the house is a shrine to the pursuit of happiness--a ranch-style emblem of the good life Darrell and 700,000 other U.S. soldiers fought for in the Persian Gulf four years ago.

Inside, the evil shows itself at once. It has taken up residence in the body of the Clarks' three-year-old daughter, Kennedi.

On a Saturday afternoon, Darrell and Shana huddle in their paneled living room.

They are in their mid-twenties, robust and suntanned, but their eyes are older.

Kennedi toddles about, pretending to snap pictures. You see the evil's imprint

when she lowers the toy camera: Her face is grotesquely swollen, sprinkled with

red, knotted lumps.

On a Saturday afternoon, Darrell and Shana huddle in their paneled living room.

They are in their mid-twenties, robust and suntanned, but their eyes are older.

Kennedi toddles about, pretending to snap pictures. You see the evil's imprint

when she lowers the toy camera: Her face is grotesquely swollen, sprinkled with

red, knotted lumps.

Kennedi was born without a thyroid. If not for daily hormone treatments, she would die. What disfigures her features, however, is another congenital condition: hemangiomas, benign tumors made of tangled blood vessels. Since she was a few weeks old, they have been popping up all over--on her eyelids and lips; in her throat and spinal canal. Laser surgery shrinks them, but they return again and again. They distort her speech, threaten her life. And, inevitably, they draw the stares of strangers. "When people see her," says Shana, "they say, 'Ooh, what happened to your baby?'"

Neither Shana nor her husband can answer that question conclusively, but they suspect that Kennedi's troubles have their origins in the Gulf, where Darrell served as an Army paratrooper. During operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm, he faced a mind- boggling array of environmental hazards. Like an estimated 45,000 of his comrades, he has developed symptoms--in his case, asthma and recurring pneumonia--linked to an elusive affliction known as Gulf War syndrome. And like a growing number of Gulf War veterans, some of whom remain apparently healthy, he has fathered a child with devastating birth defects.

[The veterans] need to keep the pressure on because . . . the companies who stand to be found liable will be in there lobbying."

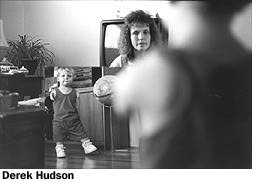

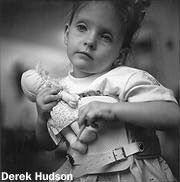

Jayce is remarkably agile. He can feed himself marshmallows (above) or shimmy

quickly across a floor. But learning to walk on prosthetic legs (right) is

terribly difficult without arms to use for balance. Jayce's mother, Connie

(left), holds up a mirror to help him with coordination. A devout Christian, she

faces her family's troubles stoically. "I accept what God has given us," she

says, "and try to make the best of it."

Jayce is remarkably agile. He can feed himself marshmallows (above) or shimmy

quickly across a floor. But learning to walk on prosthetic legs (right) is

terribly difficult without arms to use for balance. Jayce's mother, Connie

(left), holds up a mirror to help him with coordination. A devout Christian, she

faces her family's troubles stoically. "I accept what God has given us," she

says, "and try to make the best of it."

Researchers have been probing Gulf War syndrome since late 1991, when returning soldiers reported a spate of mysterious maladies. Conclusions have been slow to arrive. Last June the federal Centers for Disease Control (CDC) confirmed that Gulf vets were unusually susceptible to a dozen ailments--from rashes to incontinence, hair loss to memory loss, chronic indigestion to chronic pain. But in August a Pentagon study concluded that neither the vets nor their loved ones showed signs of any "new or unique illness." Veterans' advocates disputed that finding, as did the National Academy of Sciences' Institute of Medicine, which declared that the report's "reasoning . . . is not well explained." And while there is, as yet, no absolute proof that Gulf vets' babies are especially prone to congenital problems, patterns of defects have begun to emerge--patterns unlikely to result from chance alone.

During the past year, LIFE has conducted its own inquiry into the plight of these children. We sought to learn whether U.S. policies put them at risk and whether the nation ought to be doing more for them and their families. We also aimed to determine whether, as some scientists and veterans allege, the military's own investigation is deeply flawed.

The future of this country's volunteer armed forces--institutions dependent on citizens' willingness to serve, and therefore on their trust--may rest on the answers to such questions. Certainly, soldiers expect to forfeit their health, if necessary, in the line of duty. But no one expects that of a soldier's kids.

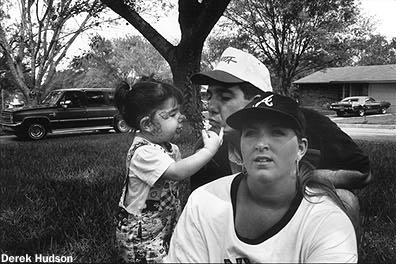

"When people see her they say, 'What happened to your baby?'" -SHANA CLARK

![]()

"Adults are worse than children as far as staring," says mom Shana. Kennedi's dad, Darrell, tested positive for radiation exposure, but unless his testes are dissected no link to her condition can be proved.

Lea' Arnold was not born to a soldier, but she might as well have been: Her father went to the Gulf as a civilian helicopter mechanic with the Army's 1st Cavalry Division. On a Wednesday morning, Lea' lies naked in her parents' bed, in a small house off a gravel road in Belton, Tex. A nurse looms over her, brandishing a plastic hose.

"Don't hurt me," wails Lea.

"I'm not going to hurt you, sweetie," says the nurse. "You need to peepee."

As the nurse administers the catheter, Lisa Arnold--a sturdy woman who carries her sadness on broad shoulders--tells the story of her daughter's birth. "The doctor said, 'Well, she's got a little problem with her back.' They let me hold her for a minute, and then they took her to intensive care." Lea' had spina bifida, a split in the backbone that causes paralysis and hydrocephalus, or water on the brain. She needed surgery to remove three vertebrae. "They told us that if she lived the next 36 hours, she'd have a pretty good chance of surviving. Those 36 hours . . . it's kind of indescribable what that's like."

Three years later, Lea' has grown into a redhead like her mother, with the haunted face of a medieval martyr. She cannot move her legs or roll over. A shunt drains fluid from her skull. "She tells me every night that she wants to walk," says Richard Arnold, a soft-spoken ex-Marine.

Richard, who had fathered two healthy children before he went to war, was working for Lockheed in the Gulf. But he bunked in the desert with the troops--and that meant swallowing, inhaling and otherwise absorbing some very dicey stuff. According to a 1994 report by the General Accounting Office, American soldiers were exposed to 21 potential "reproductive toxicants," any of which might have harmed them as well as their future children. They used diesel fuel to keep down sand. They marched through smoke from burning oil wells. They doused themselves with bug sprays. They handled a toxic nerve-gas decontaminant, ethylene glycol monomethyl ether. They fired shells tipped with depleted uranium. Other teratogens--materials that cause birth defects--may have been present too. One possibility is that desert winds bore traces of Iraqi poison gas.(POISON IN THE DESERT and POISON IN THE AIR)

Some physicians who have treated Gulf vets believe they may be suffering from a general overload of chemical pollutants--and that their body fluids are actually toxic. (Indeed, many veterans' wives are sick; a few complain that their husbands' semen blisters their skin.) "It was a toxic environment," says Dr. Charles Jackson, staff physician for the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Tuskegee, Ala. Other doctors, while agreeing that chemicals or radiation may have caused birth defects, think the vets' ills came from a germ--an unknown Iraqi biological warfare agent, perhaps, or some form of leishmaniasis, a disease carried by sand flies.

Government scientists generally discount these theories. "The hard cold facts" are simply not there, says Dr. Robert Roswell, executive director of the Persian Gulf Veterans Coordinating Board. But one hypothesis elicits even his respect. "The one argument that does deserve further study [concerns] the combination of pyridostigmine bromide with pesticides."

Pyridostigmine bromide--or PB--is a drug usually prescribed to sufferers of myasthenia gravis, a degenerative nerve disease. But animal experiments have shown that pretreatment with PB may also provide some protection from the nerve gas soman. The U.S. military therefore gave the drug to most Americans in the Gulf. Darrell Clark, for instance, took it, and Richard Arnold--now racked with chronic joint pain--probably did: "I took everything the First Cavalry took."

"Everything we hoped for just crashed. Why us? Why Cedrick?" -BIANCA MILLER

![]()

His five-year-old sister, Larissa, must be careful when they play together: A fall could dislodge the shunt in his head and lead to brain damage. Cedrick's handicaps have left his parents, Steve and Bianca, terrified of having more children.

The Defense Department may have been taking a big chance with PB. In earlier, small-scale safety trials, Air Force pilots had reported serious side effects, including impaired breathing, vision, stamina and short-term memory. (Many soldiers would experience such symptoms during the Gulf War.) Even more alarming, PB was known to worsen the effects of some kinds of nerve gas (see POISON IN THE MIX). Nonetheless, as war threatened, the Pentagon persuaded the Food and Drug Administration to waive its prohibition on testing a drug for new purposes without the subjects' "informed consent." FDA deputy commissioner Mary Pendergast defends that ruling: "You can't have your troops being the ones to decide whether they'll take some step to keep themselves healthy."

If PB did cause lasting problems, the reason could be the way it interacts with bug spray. In 1993, James Moss, a scientist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, found that when cockroaches are exposed to PB along with the common insect repellent DEET--used in the Gulf--the toxicity of both chemicals is multiplied. Moss says he pursued his experiments in spite of orders to stop. His contract wasn't renewed when it expired last year, and the researcher claims he was blackballed. (USDA Secretary Dan Glickman says Moss's "temporary appointment" was up and Moss knew it.) Since Moss's study, two others--one by the Pentagon itself, the second by Duke University--have found neural damage in rats and chickens exposed to another chemical cocktail, this one a mixture of PB, DEET and permethrin, an insecticide. Permethrin, however, was probably used by no more than 5 percent of U.S. soldiers in the Gulf.

Pentagon officials deny that any PB-DEET mixture could have caused birth defects in male Gulf vets' children. "I'm not aware that a male can be exposed to a chemical agent, and then two years later his sperm creates a defect," says Dr. Stephen Joseph, assistant secretary of defense for health affairs. But some chemicals, such as mustard gas, have been shown to affect sperm production for even longer periods. Clearly, further research is needed to determine whether a PB-and-bug-spray combo can behave the same way.

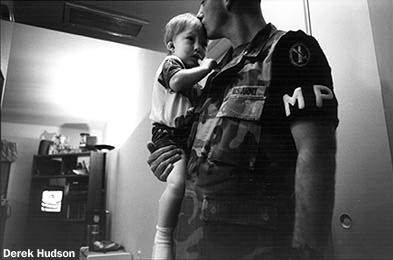

Army Sgt. Brad Minns is pretty sure he didn't take PB, but he did take a vaccine meant to save his life if Iraq resorted to germ warfare. He fears that this medication caused his chronic fatigue--and that his Gulf War service ultimately blighted his baby's life at the root.

In their bungalow at Fort Meade, Md., Brad and his wife, Marilyn, list their son's tribulations. Casey was born with Goldenhar's syndrome, characterized by a lopsided head and spine. His left ear was missing, his digestive tract disconnected. Trying to repair his scrambled innards, surgeons at Walter Reed Army Medical Center damaged his vocal cords and colon, say Brad and Marilyn. (Ben Smith, a spokesman for Walter Reed, says, "A claim has been filed by the family, and until it's resolved [the case] is in the hands of the lawyers.") Now 26 months old, Casey speaks in sign language. His parents feed him and remove his wastes through holes in his belly. Otherwise, he's a regular kid, tearing about the sparsely decorated room, shoving pens, books, scraps of paper into his mouth. Marilyn follows, tugging them out again.

"A lot of parents have anxieties about coming forth"

![]()

Born with organs out of place, he suffered further damage in surgery, says his father, Brad. Now Casey's chest has stopped growing, leading to fears that he may need an operation at some point to preserve function in his lungs.

"He's a little terror," says Brad, with the weariest of smiles.

A military policeman posted mainly at an airfield in Saudi Arabia, Brad, along with 150,000 other American soldiers, took a vaccine--on his commander's orders--against weapon-borne anthrax. A second vaccine, against botulism, was administered to 8,000 soldiers. A staff report issued last December by the Senate Committee on Veterans' Affairs concluded that "Persian Gulf veterans were . . . ordered under threat of Article 15 or court-martial, to discuss their vaccinations with no one, not even with medical professionals needing the information to treat adverse reactions from the vaccine." The Senate report noted that the particular botulinum toxoid issued "was not approved by FDA." Other details from the survey: Of responding veterans who had taken the anthrax vaccine, 85 percent were told they could not refuse it, and 43 percent experienced immediate side effects. Only one fourth of the women to whom it was administered were warned of any risks to pregnancy. Of all responding personnel who had taken the antibotulism medicine, 88 percent were told not to turn it down and 35 percent suffered side effects. None of the women given botulinum toxoid were told of pregnancy risks. "Anthrax vaccine should continue to be considered as a potential cause for undiagnosed illnesses in Persian Gulf military personnel," said the report in one of its summations. And in another: "[The botulism vaccine's] safety remains unknown."

In a conference room at the Womack Army Medical Center in Fort Bragg, N.C., Melanie Ayers is addressing a support group for parents of Gulf War babies. "Sometimes," she says, "I wish I'd gone into a corner and stayed naive." Pixie-faced and preternaturally energetic, Ayers, 30, dates her loss of innocence to November 1993, when her five-month-old son died of congestive heart failure. Michael, who was conceived after his father, Glenn, returned from action as a battery commander in the Gulf, sweated constantly--until the night he woke up screaming, his arms and legs ice-cold. His previously undetected mitral-valve defect cost him his life.

After Michael's death, Melanie sealed off his bedroom; she tried to close herself off as well. But soon she began to encounter "a shocking number" of other parents whose post-Gulf War children had been born with abnormalities. All of them were desperate to know what had gone wrong and whether they would ever again be able to bear healthy babies. With Kim Sullivan, an artillery captain's wife whose infant son, Matthew, had died of a rare liver cancer, Melanie founded an informal network of fellow sufferers.

Surrounded by framed photos of decorated medics and nurses, a dozen of those moms and dads have come to share their worries, anger and grief. Kim is here. So is Connie Hanson, wife of an Army sergeant; her son, Jayce, was born with multiple deformities. Army Sgt. John Mabus has brought along his babies, Zachary and Andrew, who suffer from an incomplete fusion of the skull. The people in this room have turned to one another because they can no longer rely upon the military.

"They told us that if she lived the next 36 hours, she'd have a pretty good chance of surviving. Those 36 hours. . . . It's kind of indescribable what that's like." -LISA ARNOLD

Spina bifida cripples her legs. Her upper body is so weak that she can't push herself in a wheelchair on carpeting. To strengthen her bones, she spends hours in a contraption that holds her upright. Brothers Nathan (in tree) and Joey, both born before the war, are healthy. "The boys care a lot about Lea'," says her mom, Lisa. "Every time she goes to the hospital, their schoolwork suffers."

"A lot of the parents have had anxieties about coming forth with their concerns," says Dr. Sharon Cooper, the Womack Center's director of pediatrics. Cooper is one military official who, rather than taking an adversarial stance, is dedicated to helping Gulf veterans and their families cope. Many vets speak of Army physicians who dismiss physical ailments as symptoms of stress, even as fabrication. They cite an internal report by the National Guard, leaked to the press last year, which revealed that hundreds of Gulf vets had been wrongly discharged as a money-saving measure--let go with a supposedly clean bill of health, although ongoing medical problems entitled them to remain in the service for treatment. A second report, issued by the GAO earlier this year, scores the Veterans Administration for being routinely tardy with its payments to ailing vets. "When you send a veteran off to do dangerous work, I think his complaints deserve respect," says West Virginia Sen. Jay Rockefeller. "The phrase I've used is 'reckless disregard.' There's a stark pattern of Defense Department recklessness."

For vets with afflicted babies, the runaround can be just as bad. Military doctors often ignore signs of inborn disorders, say Gulf War parents, or refuse to discuss them frankly. And when they do talk about birth defects, the doctors--and Pentagon bureaucrats--are quick to cite a statistic that drives these parents wild: At least 3 percent of American babies are born with abnormalities. To which Melanie Ayers responds: "I'd like to put my child's picture in front of them and say, 'Glance at that once in a while to make sure you're telling me the truth.'"

"There's a stark pattern of Defense Department recklessness." -SEN.JAY ROCKEFELLER

"Just about our whole world is centered around Lea'," says Lisa Arnold. Huge medical bills--and the unwillingness of insurance companies to cover preexisting conditions-- force the family to live in poverty to qualify for Medicaid.

Indeed, the truth may not be as simple as "at least three percent" implies. On a blazing Saturday afternoon, flanked by his parents, three-year-old Cedrick Miller is dangling his feet in an apartment-complex pool in San Antonio. Flossy-haired and shy, he looks younger than his age. Cedrick was born with his trachea and esophagus fused; despite surgery, his inability to hold down solid food has kept his weight to 20 pounds. His internal problems include hydrocephalus and a heart in the wrong place. But it's clear from one look that something else is awry.

Cedrick suffers, like Casey Minns, from Goldenhar's syndrome. The left half of his face is shrunken, with a missing ear and a blind eye. His mother, Bianca, says that when a prenatal exam showed the defects, "everything we'd hoped for just crashed. What had Cedrick done to deserve this?"

Steve Miller, a former Army medic, thinks chemicals damaged his sperm. He believes statistical evidence is at hand. "With Goldenhar's," he says, "we have clustering."

Clustering is the term epidemiologists use when an ailment strikes one group of people more than others--and the phenomenon can be a key indicator that something more than chance is causing birth defects. The Association of Birth Defect Children says it has found the first cluster of defects in the offspring of U.S. Gulf veterans: 10 babies with severe Goldenhar's syndrome, a condition that usually strikes one in 26,000, according to ABDC executive director Betty Mekdeci. (Another case has surfaced in Britain, where 600 vets complain of Gulf-related illness.) The ABDC, which has gathered data on 163 ailing Gulf War babies so far, is tracking four more possible clusters--of victims of hypoplastic left heart syndrome, of atrial-septal heart defect, of microcephaly and of immune-system deficiencies. Significantly, not one of the parents in the ABDC survey has a family history of these types of birth defects. Or as Mekdeci puts it, "There have been no relatives with funny ears."

The difficulty in proving conclusively whether clusters are occurring is that no one--not Mekdeci, not the Pentagon--knows how many babies have been born to Gulf vets. The Defense Department's own survey of 40,000 birth outcomes, initial results of which are due in late October, is the largest study yet, but far from complete since it relies on data only from military hospitals. The Pentagon's Dr. Joseph says the forthcoming report will include "by far the best and most comprehensive information available." Maybe it will, but many still question whether Defense Department scientists are really seeking the hard answers. Earlier this year Dr. Joseph told LIFE that, although trained as a pediatrician, he was entirely unfamiliar with "Goldhavers or Gold Heart--whatever." It's precisely that kind of response that enrages veterans with afflicted babies.

Along with the ABDC and Defense Department surveys, more than 30 other studies of Gulf vets and their children are under way. One that is no longer ongoing, by the Senate Banking Committee, folded last year when committee chair Don Riegle retired. Of the 400 sick vets who had already answered committee inquiries, a startling 65 percent reported birth defects or immune-system problems in children conceived after the war.

"A millionaire couldn't care for these kids." -LISA ARNOLD

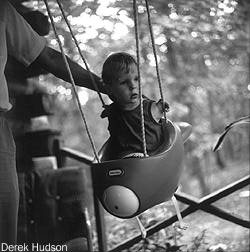

An airplane swing sets Jayce free.

An airplane swing sets Jayce free.

Although Riegle is gone, there are a few others in Washington fighting for afflicted Gulf War families. One is Rockefeller, but in recent months he has lost clout. After last year's GOP landslide, he was ousted as chairman of the Veterans' Affairs Committee, which produced the 1994 report on PB and vaccine use in the Gulf. The new chair, Alan Simpson (R--Wyo.), plans no action "until the hard science is in," says an aide.

Then there is Hillary Rodham Clinton, the point person for an administration that, by pushing through a 1994 law mandating benefits for vets with symptoms, has cast itself as a friend of Gulf War syndrome sufferers. On August 14, at the opening session of the presidential advisory committee on the syndrome, she declared, "Just as we relied on our troops when they were sent to war, we must assure them that they can rely on us now."

Whatever White House fact finders discover, there's no guarantee that Gulf War babies will get government help. As it stands, a soldier's children receive free medical care only as long as a parent remains in the service. For parents who return to civilian life, the going can be grim. Moreover, the government's record on earlier military health grievances is hardly reassuring. Soldiers unwittingly used in radiation experiments in the 1950s, for instance, had to fight the VA for compensation until the 1980s. And Vietnam veterans claim that scientists manipulated evidence to hide the ravages of Agent Orange. "The CDC actually skewed the data," says retired Navy Adm. Elmo Zumwalt Jr., who blames his son's fatal cancer on the defoliant. Vietnam vets won a $180 million settlement from Agent Orange manufacturers, but not until 1984. Gulf vets, says Zumwalt, "need to keep the pressure on, because in the case of Agent Orange--and I'm sure it'll occur with Desert Storm syndrome--the companies who stand to be found liable for any harmful effects will be in there lobbying."

A few Desert Storm families have been relatively lucky--the Clarks, for instance, whose daughter has been granted free treatment through November of 1996, thanks to an Air Force doctor who recommended her as a subject for study. But others have been denied insurance coverage for "preexisting conditions." They are being driven into poverty; some join the welfare line so Medicaid will help with the impossible burden. "You could be a millionaire, and there's no way you could take care of one of these children," says Lisa Arnold.

Betty Mekdeci thinks Congress should set up a special insurance fund for families like the Arnolds. "The very least we owe these folks is to provide them with a guarantee of care," she says. "I'd be glad to pay the extra taxes to do it.""

"I'm angry, frustrated and sad," says Darrell Clark. "It's unfortunate that no one will speak up and say, 'Maybe we made a mistake. How can we help you get on with your lives?'"

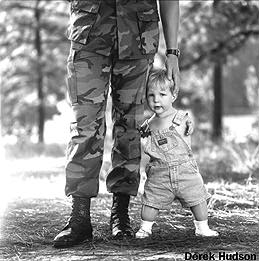

Packed into an airplane-shaped swing at his grandmother's house in Charlottesville, Va., Jayce Hanson is getting on with his life as best he can. A cherubic, rambunctious blond, he's the unofficial poster boy of the Gulf War babies--seen by millions in People. Jayce is the center of attention here, too, as his father pushes the swing and a photographer snaps his picture. But since his last major public appearance, he has undergone a change: His lower legs are missing.

Now three years old, Jayce was born with hands and feet attached to twisted stumps. He also had a hole in his heart, a hemophilia-like blood condition and underdeveloped ear canals. Doctors recently amputated his legs at the knees to make it easier to fit him with prosthetics. "He'll say once in a while, 'My feet are gone,'" says his mother, Connie, "but he's been a real trouper."

During the war, Paul Hanson breathed heavy oil smoke; he stopped taking PB pills early, because they made him dizzy. Now he suffers regularly from headaches, nausea, tightness in the chest. Still, he is optimistic for his son.

"Jayce is very bright," says Paul. "He doesn't realize his limitations. But when he grows up and says, 'Why am I not like everybody else?' we'd like to be able to explain it to him."