Patients hold a spoon-shaped antenna in their mouths to deliver a very low-intensity electromagnetic field in their bodies. In trials of patients with advanced liver cancer, the therapy – given three times a day – resulted in long-term survival for a small number of those monitored, the team has reported in the British Journal of Cancer. Their tumours shrank, while healthy cells in surrounding tissue were unaffected.

However, the scientists – from the US, Brazil, France and Switzerland – also stressed that the technique was still in its infancy and would require several years for further trials to take place. "This is a truly novel technique," said the team's leader, Professor Boris Pasche of the University of Alabama, Birmingham. "It is innocuous, can be tolerated for long periods of time, and could be used in combination with other therapies."

Pasche added that he had obtained permission from the US Food and Drug Administration to carry out trials on large groups of patients and was talking to companies in the US, Asia, South America, Russia and Europe about raising funds for future research.

In 2009, Pasche and his colleagues published results in the Journal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer Research which showed that low-level electromagnetic fields at precise frequencies – ranging from 0.1Hz to 114kHz – halted cancer cell growth in small numbers of patients. Different cancers responded to electromagnetic fields of different frequencies. Cells in surrounding, healthy tissue were unaffected.

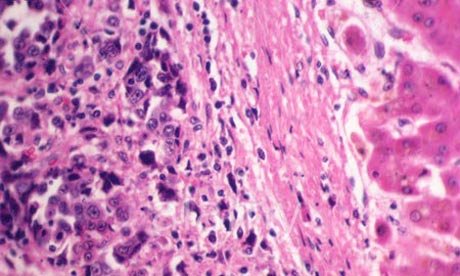

The exact mechanism for this process was not explained in the paper. However, results of recent experiments by the team – using cancer cell cultures in the laboratory and published in the British Journal of Cancer – suggest that low-level electromagnetic fields interfere with the activity of genes in cancer cells. In specific cases, this affected the ability of cancer cells to grow and divide. The spread of tumours halted and in some cases they began to shrink.

"This is extremely exciting," said Pasche. "We think the technique could also be used to treat breast tumours and possibly other forms of cancer."

The use of electromagnetic fields was also welcomed, cautiously, by Eleanor Barrie of Cancer Research UK: "This research shows how specific low frequencies of electromagnetic radiation can slow the growth of cancer cells in the lab. It's still unclear why the cancer cells respond in this way, and it's not yet clear if this approach could help patients, but it's an interesting example of how researchers are working to find new ways to home in on cancer cells while leaving healthy cells unharmed."

The use of electromagnetic fields to treat tumours may seem surprising given recent controversy over claims that fields generated by mobile phones and electricity pylons can trigger cancers and leukaemia. However, Pasche stressed that the intensity of the fields used in his team's experiments were between 100 and 1,000 times lower than those from a mobile phone. "In any case, the evidence produced from major studies of users of these phones does not suggest there is a clearly identifiable risk posed by these electromagnetic fields," he said.