Towards the end of the war, scientists at an institute in Dachau conducted research into how malaria-infected insects could be kept alive for long enough to be released into enemy territory.

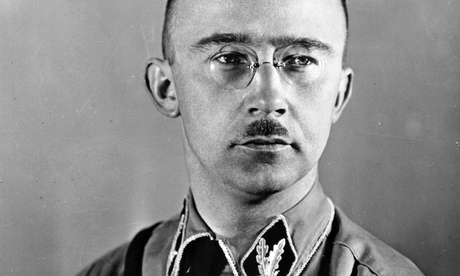

In January 1942, the leader of the SS, Heinrich Himmler, ordered the creation of the Dachau entomological institute. Its official mission was to find new remedies against diseases transmitted by lice and other insects: German troops were often plagued by typhoid, and there were concerns about a developing typhoid epidemic at the Neuengamme concentration camp.

But in an article for the science journal Endeavour, Klaus Reinhardt says protocols kept by the head of the institute allow no other conclusion than that the institute also pursued research into biological warfare.

In 1944, scientists examined different types of mosquitoes for their life spans in order to establish whether they could be kept alive long enough to be transported from a breeding lab to a drop-off point. At the end of the trials, the director of the institute recommended a particular type of anopheles mosquito, a genus well-known for its capacity to transmit malaria to humans.

With Germany having signed up to the 1925 Geneva protocol, Adolf Hitler had officially ruled out the use of biological and chemical weapons during the second world war, as had allied forces. Research into the mosquito project had to be carried out in secret.

In the end, the research proved of little value. Behind the project was "a bizarre mix of Himmler's smattering of scientific knowledge, personal paranoia, an esoteric world view, and genuine concerns about his SS troops", Reinhardt told Süddeutsche Zeitung. In comparison with the biological research of the allied forces, he said, Nazi research had been "risible".

Animals were frequently employed for military operations during the first and second world war, though mainly for transport and communication. In 2004, the British government unveiled a memorial dedicated to the animals including horses, dogs and pigeons who served and died alongside British and allied troops.

During the first world war, glow worms were often kept by British soldiers to help them read maps at night. American researchers also worked on a plan to use bats to carry incendiary bombs, but the programme was shelved.