"My grandfather was an Osu," he says.

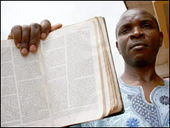

He is standing outside his church in Enugu, south-eastern Nigeria, clutching his Bible which he believes has saved him from being a marked man.

Among the Igbo people of eastern Nigeria the Osu are outcasts, the equivalent of being an "untouchable".

Years ago he and his family would be shunned by society, banished from communal land, banned from village life and refused the right to marry anyone not from an Osu family.

Marriage

The vehemence of the tradition has weakened over the last 50 years.

Nowadays the only trouble the Osu encounter is when they try to get married.

But the fear of social stigma is still strong - to the point that most would never admit to being an Osu.

They fear the consequences for their families in generations to come or at the hands of people who still believe in the old ways.

It took the BBC a long time track down an Osu willing to talk, Igbo journalists, human rights advocates, academics and politicians could suggest no-one.

It was only by chance that Cosmos admitted his family were Osu after an interview with the Pentecostal church - known to oppose the tradition.

Now a born-again Christian, he has had a hard fight to escape the stigma of the Osu.

Sacrifice

People say the Osu are the descendants of people sacrificed to the gods, hundreds of years ago.

But an academic who has researched Igbo traditions says he believes the Osu were actually a kind of "living sacrifice" to the gods from the community.

"I remember when I was a child, seeing the Osu and running away," says Professor Ben Obumselu, former vice-president of the influential Igbo organisation Ohaneze Ndi Igbo.

"They were banned from all forms of civil society; they had no land, lived in the shrine of the gods, and if they could, would farm the land next to the road."

"It was believed that they had been dedicated to the gods, that they belonged to them, rather then the world of the human," he said.

Nigeria's growing cities began to break down such traditions of village life, he says.

"If someone lives in Lagos these days, the only time a person may come into contact with it is when they are planning to get married. They go home to tell their families, their parents turn around and say, 'No you can't marry because they're Osu.'"

Initiated

Cosmos' father had denounced the traditional beliefs that made him an outcast from society.

He raised Cosmos to be a Christian too, hoping the bloodline of the Osu would be broken.

But when Cosmos was a child his grandfather died and at around the same time Cosmos fell sick.

"The village said the reason I was ill was I was being possessed by the spirit of my grandfather, and he was angry that we had rejected the old ways," he said.

The village elders put pressure on his father to initiate Cosmos into the old traditions and culture.

It was either that, or he would die, they said.

So he left church, learnt about the spirits and his status in the village.

Outlaw

But this ostracism, he now believes, left him without "moral direction".

He became an itinerant smuggler and outlaw, bringing in goods illegally over Nigeria's northern border from Niger.

Eventually he was arrested and thrown in jail.

"It was in the prison yard that I was born again," he said.

"When I believed in the old ways, I could not marry or be part of my community," he said.

"Now I've been born again, I have rejected all that, and my wife, she is born again too, and doesn't care about it either."

His wife's family had also rejected the traditions of the Osu and did not object to their daughter's choice of husband.

Education advantage

Other Osu have been able to use the ostracism to their advantage, says Mr Obumselu.

Unable to make a way in village life, some Osu embraced "Western" education and became Nigeria's first doctors and lawyers, he says.

Consequently many of modern Igboland's prominent families are Osu.

So why does the stigma remain?

Mr Obumselu says the traditions have a lingering hold on people because they are not sure how much power the "old ways" still have.

Traditionally the Osu are treated as a people apart, but were never the victims of violence.

But today some community conflicts have erupted between people each accusing the other of being Osu, Mr Obumselu says.

"The continued belief in ritual avoidance has caused great harm to society, especially in Enugu."

Pentecostal churches, like Mr Chiedozie's, are having an effect and a growing population may also drown out the stigma of being Osu, says Mr Obumselu.

"After all, if in 1800 there might only be a handful of Osu in any place, in 2000 it may be a third of the village!"

Comment: Ritual avoidance comes in all sorts of shapes and sizes. While not to detract from his laudable efforts at social inclusion, what a pity that the good pastor can't see that the book he's holding actually promotes social exclusion, if not genocide - a tradition that remains strong even among the unreligious, e.g. in Israel's murderous dealings with the Palestinians. How far back in history does this desire to exclude others go? How strong is it still in each of us?