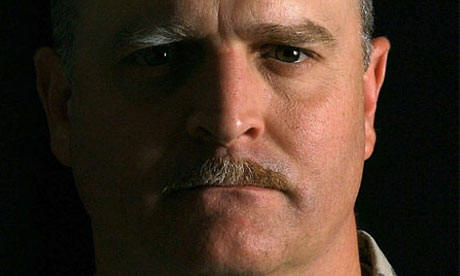

The career soldier is now a black sheep at the giant defence department building where he still works. The reason was his extraordinarily brave decision to accuse America's military top brass of lying about the war in Afghanistan. When he went public in the New York Times, he was acclaimed as a hero for speaking out about a war that many Americans feel has gone horribly awry. Later this month he will receive a Ridenhour prize, an award given to whistleblowers that is named after the Vietnam war soldier who exposed the My Lai massacre.

Davis believes people are not being told the truth and said so in a detailed report that he wrote after returning from his second tour of duty in the country. He had been rocketed, mortared and had stepped on an improvised explosive device that failed to explode. Soldiers he had met were killed and he was certain that a bloody disaster was unfolding. So he spoke out. "It's like I see in slow motion men dying for nothing and I can't stop it," he said. "It is consuming me from the inside. It is eating me alive."

Davis, 48, drew up two reports containing research and observations garnered from his last tour. He was not short of material. As part of his job he had criss-crossed the country, travelling 9,000 miles and talking to more than 250 people. He had built up a picture of a hopeless cause; a country where Afghan soldiers were incapable of holding on to American gains. US soldiers would fight and die for territory and then see Afghan troops let it fall to the Taliban. Often the Afghans actively worked with the Taliban or simply refused to fight. One Afghan police officer laughed in Davis's face when asked if he ever tried to fight the enemy. "That would be dangerous!" the man said.

Yet at the same time Davis saw America's military chiefs, such as General David Petraeus, constantly speak about America's successes, especially when working with local troops. So Davis compiled two reports: one classified and one unclassified. He sent both to politicians in Washington and lobbied them on his concerns. Then in February he went public by giving an interview to the New York Times and writing a damning editorial in a military newspaper. Then – and only then – did he tell his own army bosses what he had done.

Davis pulled no punches. His report's opening statement read: "Senior ranking US military leaders have so distorted the truth when communicating with the US Congress and American people in regards to conditions on the ground in Afghanistan that the truth has become unrecognisable."

The report detailed an alarming picture of Taliban advances and spiralling violence. Afghan security forces were unwilling or unable to fight, or actively aiding the enemy. That picture was contrasted with repeated rosy statements from US military leaders. His classified version was far more damning, but it remains a secret. "I am no WikiLeaks guy part two," Davis said. He foresees a simple and logical end point for Afghanistan – civil war and societal collapse, probably long before the last US combat soldier is scheduled to leave. He says the Afghan army and police simply cannot cope and the US forces training and working with them know that, despite official pronouncements to the contrary. "What I saw first hand in virtually every circumstance was a barely functioning organisation often co-operating with the insurgent enemy," Davis's report said.

The document was also damning about the role of the US media in reporting the war. Ever since Vietnam, generals have slammed the press as a potential danger to military operations, but Davis's report lambasted journalists for failing to question the official army line. He said the media were obsessed with getting "access" to military bases and generals and tempered reporting in order to maintain that situation. "Most of the media just takes the talking points and repeats them," he said.

Davis has not been officially sanctioned – because his classified report remains secret, he broke no law – and the military has not set out actively to condemn him. Instead there has been a muted official response, while privately, Davis said, many colleagues have congratulated him for speaking out. Yet he is now experiencing a strange end to a military career to which he devoted his life. It included serving in Germany, both Iraq wars and then two tours in Afghanistan. He said it gave him pride and a sense of purpose in doing a greater good.

"I loved the army. There was nothing I have ever wanted to do more than this job since I started as a private back in 1985," he said. That is a very all-American sentiment, but then so is Davis's background. He was born the son of a football coach and grew up in Dallas, Texas. He is a born-again Christian who sings in a church choir. He said the decision to go public involved heavy "soul-searching".

It has also made any future career advancement highly unlikely. "Maybe no one will listen, but I would not be able to sleep if I made no attempt," he said.

What Davis wants – and what several politicians are lobbying for – are congressional hearings on the issue. He wants the generals grilled on his report and on how their comments compare with the evidence. But that needs the support of party leaders such as Democratic senator Harry Reid or Republican House speaker John Boehner, and that seems unlikely because such hearings would be a political minefield.

This only serves to infuriate Davis. "Wouldn't you want to know the truth when you are making a war-and-peace decision?" Does he have any regrets? "There has never been a fraction of a question as to whether I did the right thing," he said. "Lives are at stake."