Parvovirus

Everything you wanted to know…and some things you wish you didn’t

By: Patricia Jordan DVM,

Catherine O'Driscoll and Dana Scott

July/August 2011

http://www.dogsnaturallymagazine.com/parvovirus-2/

Back in June of 1997, the Sunday Times featured an article by Clare Thompson about emerging viruses, with the heading: “DEAD RECKONING” Beneath the title, the summary stated: “New killer viruses are emerging every year, unleashed by the very medical and technological advances that promised to control our environment. Nature may be telling us to stop, but who is listening?”

The article went on to state “Newly emerging viruses are now the biggest threat to mankind. In the past 20 years, scientists have discovered around 30 new diseases, a staggering rate of one or two each year, most of them spread from animals to man. All are immune to antibiotics, and they can mutate so fast that the handful of antiviral drugs available quickly become obsolete.”

“Medical technology has spawned its own demons…there is no doubt that new medical developments, such as vaccines grown in animal cells or animal-to-human transplants, might easily contribute to an epidemic.” The article then offered an interesting example of a man-made epidemic that directly affects our dogs: it stated that parvovirus was created when vaccine manufacturers cultivated the distemper vaccine on infected cats’ kidneys.

In 1978, dogs around the world suddenly began to die, developing bloody diarrhea and rapidly (often overnight), progressing to fatal dehydration. Canine parvovirus arrived and exploded round the world within a few mere months, infecting millions and killing thousands of dogs. “Most viruses go into a new host and just die out,” says Laura Shackelton, a postdoctoral researcher at Pennsylvania State University, who has studied the evolution of parvovirus in both dogs and cats. “This one took off.” How could this happen?

Canine parvovirus is very similar to the long known feline panleukopenia virus (FPV). Soon after its appearance, parvo was classified as a mutation of FPV – in fact, the first vaccines used against parvo were FPV vaccines. Prior to the parvovirus outbreak, the only widely-used vaccine for dogs was distemper. At some point, cats’ kidneys were used to develop the distemper vaccine and this was shipped around the world and injected into dogs. If Clare Thompson is right, the distemper vaccine was grown on cat kidney cells and the cats were infected with FPV.

Another possibility is that cats that were vaccinated for FPV shed that vaccine through their feces – a very real risk with modified live vaccines. The feline parvovirus could have easily mutated into canine parvovirus. In Vaccines For Biodefense And Emerging And Neglected Diseases, the authors state that the trouble with modified live vaccines is: “…there is a high probability of back mutation and reversion to virulence once introduced to the animals.”

Regardless of how canine parvovirus originated, it is well accepted that it is a man-made disease and it is the result of vaccination, either for canine distemper or FPV. This much is obvious because the outbreaks were sudden and massive and they first surfaced in countries that regularly vaccinated dogs and cats.

As with all “new” viruses, parvo is constantly evolving and mutating but it has a faster mutation rate than most other viruses. Today, nearly thirty-five years later, parvo remains the most common viral disease in dogs.

There are two canine parvoviruses: canine parvovirus-1 and canine parvovirus-2. CPV-2 is the primary cause of the puppy enteritis that we commonly see. Over the years, parvo has mutated from CPV-2 to CPV-2b to CPV-2c. “This wasn’t a reversion,” Shakelton notes. It seems that dogs may be getting the ultimate revenge on cats: the CPV-2c strain of parvovirus is now crossing species and infecting cats with another brand new virus.

Now that parvo is apparently here to stay and is mutating at a rapid rate, how can we protect our dogs and, most importantly, our puppies from this potentially fatal disease? Many vets and dog owners would quickly reply ‘vaccinate them!’ and that might protect your dog. But the real question is, “at what cost?”

Unvaccinated dogs have long been targeted as vectors for disease. Vets and immunologists claim we need to vaccinate at least 75% of the dog population to keep deadly viruses like parvovirus under control – they call this herd immunity. Dog owners who do not vaccinate are blamed when viruses like parvovirus continue to spread and mutate. The vets tell us that as long as there are unvaccinated dogs, parvovirus will always be in the environment. And so we vaccinate.

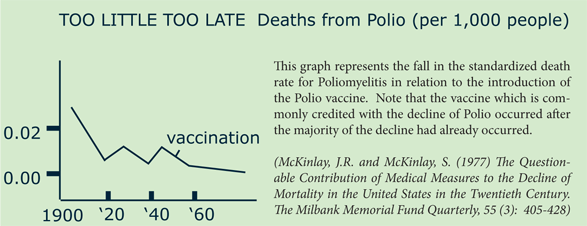

Few people have stopped to ask if the vaccine itself is responsible for the spread and mutation of parvovirus. If this seems far-fetched, take a look at the history of the polio vaccine. Poliomyelitis is a virus that attacks the spinal cord, causing muscle weakness and paralysis. When the polio vaccine was introduced in 1955, it was fully credited for the decline in polio. Like influenza, measles and whooping cough however, polio was already in decline before the vaccine was introduced. What happened with all of these diseases is exactly what happened with parvovirus.

When parvovirus hit in 1978, it exploded because dogs had never been exposed to anything like the virus and they had no immunity to it. A single exposure to parvovirus however, provided dogs with long-lasting immunity and this immunity could be passed to puppies by nursing dams. Dogs soon became immune to the initial CPV-2 virus and although that original virus is still with us today, it isn’t usually a cause of epidemics because as more dogs were exposed to the disease, they developed immunity.

The same thing happened in humans with polio, influenza, measles and whooping cough – eventually, enough people were exposed that the viruses were effectively controlled by the immune system. Many people credit the decline in mortality from these diseases to vaccination. In 1977 however, McKinlay revealed that these diseases were already in serious decline before the vaccines were ever introduced.

Getting back to polio, if we take a look at this disease today, there are some interesting and worrisome trends. Today, polio is only prevalent in a few third world countries with poor sanitation. In Nigeria, the polio vaccine is mutating and the World Health Organization is blaming the unvaccinated children. The WHO claims that the virus in the water supplies – passed by vaccinated children – is supposedly safe but is picked up and mutated by unvaccinated children, becoming a new virulent strain that is infecting both vaccinated and unvaccinated children.

As more Nigerians give in to the pressure to vaccinate however, more of their children are infected with the mutated virus. In 2007, 69 children were paralyzed and in 2009, despite more children being vaccinated, that number reached 127. A virologist with the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Olen Kew, says that there’s no difference in virulence between wild polio viruses and the mutated form. “The only difference is that this virus was originally in a vaccine vial.” What this means is that as long as children are vaccinated for polio in Nigeria, the polio virus will remain in the environment.

Official concern is that the new virus will spread beyond Nigeria’s borders into surrounding vaccinated countries, and that it will spread from there to people outside the African continent. Are we facing a new polio epidemic, caused by the vaccines sold as a panacea to prevent it?

This is not unlike what is happening with the Bird Flu virus. Virologist Chairul Anwar Nidom has done some pretty interesting research showing that mass inoculations keep the disease in the environment by:

Avian disease specialist Dr. Charles Rangga Tabbu has also spoken out against mass inoculation for the Bird Flu as a scientifically baseless policy. Veterinary pathologist Dr. R. Wasito has noted that vaccination for the Bird Flu has allowed it to mutate and that other animals including dogs, cats, racoons and flies can now carry the mutated virus.

Could the same thing be happening with parvo? According to an article in The Veterinarian by Mark Kelman, “animals that have received at least one vaccination (for parvovirus), represent 28% of puppies infected, and 11% of adults infected.” That’s a large number.

There are a lot of reasons for vaccine failure, the most relevant being blocking of the vaccine by maternal antibodies. These days, there are many high titre/low passage vaccines that claim to override maternal antibodies. The good news is, most manufacturers show that these vaccines protect most puppies when given at 12 weeks of age. The bad news is, high titre/low passage is just a fancy way of saying there is a lot more antigen (up to 65 times more) in the vaccine that will be shed into the environment through vaccinated puppies.

Ironically, another human intervention that is increasing the threat and spread of parvovirus is the use of Tamiflu to treat infected dogs. Historically, antiviral medications, like vaccinations, will result in further mutations in the virus as it adapts to its environment. Tamiflu has been banned for human use in Japan because of the high incidence of psychotic reactions. Interestingly, Tamiflu is manufactured from an extract of Chinese Star Anise; a herb which is also associated with neurological effects.

Meanwhile, as Clare Thompson predicted, parvo has continued to mutate rapidly since 1978. It has moved into a new ecosystem, and is adapting to that ecosystem in a hurry. Viruses that successfully switch hosts are rare, but potentially catastrophic. Canine parvovirus has now become a major threat to the conservation of wolves. About half of the wolf puppies in Minnesota have succumbed to canine parvovirus. Carnivore parvovirus isolates have caused disease in Lynx, bobcats and raccoons.

As tempting as it is to blame unvaccinated dogs for the spread of parvo, the fact remains that if the original CPV-2 strain was all we had to worry about, there would be only a few minor outbreaks because most of our dogs have developed immunity. But as parvo mutates through the use of modified live and recombinant vaccines, it will remain one step ahead of our dogs – and now our cats. Vaccinated dogs are virally active, and for 21 days after vaccination, they are shedding the virus every time they go out in the yard, on a walk, to the dog park, the vet’s office or to training class. And now, with their immune system compromised by the vaccine, and with the ability of recombinant vaccines to mutate and create new viruses, vaccinated dogs become a viral incubator.

Does the parvo vaccine protect our dogs? The answer is, protect them from what? There is a heart disease called cardiomyopathy that is associated with parvoviruses. Cardiomyopathy did not affect dogs before the parvovirus outbreak or was very rare. Since the parvo pandemic of 1978, cardiomyopathy is prevalent in many breeds and breeding dogs are routinely screened for this often fatal disease. It is believed that the parvovirus vaccination is likely to be the cause of most cases and that vaccination created the heart muscle association in parvo that is not seen in natural infections.

Like polio and the Bird Flu, the parvo vaccine may not only keep the virus in the environment, but it may be responsible for the new and dangerous mutations that allow it to cross back into cats and other species, transmit through the air and cause other potentially fatal diseases such as cardiomyopathy. Furthermore, 28% of vaccinated puppies still get the disease. It would appear that in the long run, parvo vaccination may create more problems than it solves. But people are myopic at times and, in our fear of our dogs dying from preventable disease, we vaccinate them today but don’t worry about what can happen tomorrow.

If there is one lesson life has to teach us, it is that life goes hand-in-hand with risk. Too many people believe they can eliminate risk with vaccination and this just isn’t the case. In a short term clinical or field study, parvo vaccination may appear protective: unfortunately, nobody is taking a long, hard look at the long-term fallout and what it can mean for our dogs, for us and for the environment.

In the September 2011 issue, we will explore the impact that parvo vaccination can have on individual dogs. Read Part 2 now.

© 2011 Dogs Naturally Magazine. This article may not be reproduced or reprinted in whole or in part without prior written consent of Intuition Publishing.