Pregnant Women Get More Ultrasounds, Without Clear Medical Need

Experts say frequent fetal scans in low-risk pregnancies aren’t medically justified

Doctors are performing fetal ultrasound on pregnant women at accelerating rates, possibly without sound medical reasons. Photo: Joshua Lott/Reuters

By KEVIN HELLIKER

July 17, 2015

During her pregnancy, Milena Mrosovsky estimates she underwent a dozen fetal ultrasounds. “I was just happy to get my pictures,” she says of the scan images, “and keep them in my little album.”

Her experience isn’t uncommon. American women have been getting fetal ultrasound scans at sharply higher rates than before, and parents have turned the images of their unborn into fixtures of social media.

In 2014, usage in the U.S. of the most common fetal-ultrasound procedures averaged 5.2 per delivery, up 92% from 2004, according to an analysis of data compiled for The Wall Street Journal by FAIR Health Inc., a nonprofit aggregator of insurance claims. Some women report getting scans at every doctor visit during pregnancy.

But medical experts are now warning that frequent scans in low-risk pregnancies aren’t medically justified. A joint statement in May 2014 from several medical societies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, calls for one or two ultrasounds in low-risk, complication-free pregnancies.

“Ultrasonogram should be used only when clinically indicated, for the shortest amount of time,” the statement said, referring to ultrasound scans, “and with the lowest level of acoustic energy compatible with an accurate diagnosis.”

A 2013 study in the journal Seminars in Perinatology, using insurance data to examine a “clearly low risk population,” found a mean of 4.55 ultrasounds per pregnancy. “In low risk pregnancies, that’s too many,” says Daniel O’Keeffe, an author of the study and executive vice president of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Had Ms. Mrosovsky known that more than two scans were unnecessary for her low-risk pregnancy, “I would certainly have asked more questions before blindly following my doctor’s lead,” says Ms. Mrosovsky, 32, of Forest Hills, N.Y., whose son is now a healthy 2-year-old.

Experts in fetal medicine have long recommended women undergo one ultrasound around the 20th week of a low-risk pregnancy, and in recent years they have come to recommend an earlier one as well, around the 12th week. About 80% of pregnancies are low-risk.

But in the 2014 statement, doctors and other scientists codified that standard of one or two ultrasounds. And even those involved in the publication of that protocol aren’t sure many obstetricians are aware of it. “Some doctors don’t read medical journals,” says Dr. O’Keeffe.

Fetal ultrasound in humans has never been shown to cause harm. But nearly all research supporting its safety was conducted using equipment made before 1992, when the procedure produced about one-eighth the acoustic energy it is allowed to emit today and when fetal-ultrasound scanning was far less frequent.

Because major epidemiological studies haven’t been done since then on fetal ultrasound, there are some unknowns about long-term effects of modern equipment. And studies have suggested many operators don’t pay close attention to safety gauges while they are performing procedures.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, warning last December against scans purveyed as keepsakes by some nonmedical businesses, said: “Ultrasound can heat tissues slightly, and in some cases, it can also produce very small bubbles (cavitation) in some tissues,” adding that “the long-term effects of tissue heating and cavitation are not known.”

Some animal experiments have suggested ill effects of ultrasound on embryos of mice and chickens. And multiple fetal ultrasounds can raise false alarms, including overestimation of fetal size that can lead to potentially unnecessary caesarean deliveries. “Increased use of prenatal ultrasound scanning may be contributing to the rising CD [caesarean delivery] rate,” said a 2012 paper in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Still, many doctors take the approach that ultrasound is inherently safe because it delivers no carcinogenic radiation, says Wayne State University obstetrician Jacques Abramowicz, who chairs the safety committee of the World Federation For Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology.

“They think, ‘It’s not X-ray. It’s safe. Period,’ ” says Dr. Abramowicz, adding that he wasn’t aware that ultrasound-usage rates were as high as the Journal found.

Modern ultrasound technology produces a more-detailed image of an unborn baby’s features, right, than one from a conventional scan of the same fetus on the same day, left. PHOTO: DR NAJEEB LAYYOUS/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Doctors warn pregnant women to avoid alcohol, hot tubs, excessive stress and other potential risks to the fetus. There haven’t been similar warnings about ultrasound, in part because they don’t want to scare women away from procedures whose medical value far outweighs any potential risks, say Dr. Abramowicz and other experts.

Now, some fetal-ultrasound experts say women should be explicitly told that—in the absence of complications or alarms—one or two is sufficient for the average low-risk pregnancy.

“The message needs to be gotten out,” says Phillip J. Bendick, an ultrasound scientist and editor of the Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography. “The public needs to be made aware that if you’re pregnant, you don’t drink alcohol, you don’t smoke and you don’t need to have an ultrasound at every doctor’s visit.”

Until recently, the pregnancy pages of Mayo Clinic’s website stated: “Routine fetal ultrasounds are considered safe for both mother and baby.” After the Journal asked it to define “routine,” Mayo changed its website to indicate one or two ultrasounds are standard in the absence of medical concerns. “In light of your questions,” a Mayo spokeswoman says, Mayo’s experts “did make some changes to clarify when fetal ultrasounds are appropriate and when they are not.”

Fetal ultrasound, first used more than a half-century ago, became commonplace by the 1980s. The device bounces sound waves off the fetus, picking up the reflections and converting them into electronic pictures.

The benefits of ultrasounds are proven. They provide a more accurate estimate of when conception began than traditional methods, helping doctors determine when to induce labor when a pregnancy has gone on too long. They can identify multiple fetuses and detect abnormalities that elevate a pregnancy’s risk level. In high-risk pregnancies, additional scans often are crucial.

And research suggests images of the unborn can help foster bonding, perhaps persuading some pregnant women to quit smoking.

Many obstetricians hew to the practice of giving one or two scans per pregnancy in the absence of medical concerns, the Journal’s interviews with doctors and parents found. The average of 5.2 ultrasounds per delivery in FAIR’s study for the Journal—culled from insurance-claim data representing more than 150 million individuals—included high-risk pregnancies, which require more scans and thus skew the number higher.

But insurance data don’t capture all fetal-ultrasound use. Some new parents interviewed by the Journal say their physicians performed more scans than they charged for, some saying they got scans on every visit. And insurance data don’t include keepsake scans at nonmedical shops.

The rising usage rates in part reflect a belief among obstetricians that routine peeks at the fetus can stave off surprises. Obstetrics pays among the highest malpractice premiums of any medical specialty, and experts in the field say it isn’t uncommon for lawsuits against obstetricians to allege that more ultrasounds should have been performed.

“You’re always afraid you’re going to miss something,” says Ingrid W. Brown, a physician near Austin, Texas, who says she performed ultrasounds at every maternal visit before discontinuing obstetrics within the past year to focus on gynecology. Dr. Brown says she kept scans brief and didn’t charge for the majority of them.

Some experts see financial motives behind frequent ultrasounds, which can cost up to several hundred dollars each and can represent significant revenue. “I suspect that some of this is padding their wallet,” says Jeffrey A. Kuller, a Duke University obstetrics professor and a practicing doctor.

Physicians’ motivations alone don’t explain why doctors exceed guidelines for ultrasound use and not for many other common tests. Americans get mammograms, colonoscopies and other medical scans at below recommended levels, according to medical research.

But ultrasound has a unique appeal for parents. Offering a magical glimpse inside the womb, it answers one of mankind’s oldest questions: What does my baby look like?

Many long to see their unborn at every doctor’s visit. “There was a time or two when it seemed as though she wasn’t going to do an ultrasound, so my husband and I requested one, and she obliged,” says Tracy Bunye of her obstetrician. A New York psychologist, Ms. Bunye, 36, says she believes regular glimpses of her unborn daughter helped foster a sense of bonding.

“When I say we only need to do as many as are clinically indicated,” says North Carolina obstetrician Laura Houston, “patients look at me like I’m being mean.”

Posting fetal images on social media has become a new rite, and obstetricians’ websites increasingly are decorated with fetal images. Ultrasound-equipment maker General Electric Corp. addresses expectant parents atop a Web page advertising its technology: “Get to Know Your Baby Before It’s Born.” GE says it markets fetal-ultrasound equipment only to health-care providers for medically necessary scans.

Wanting to see more of their unborn than their doctors allow, some parents patronize nonmedical operators that offer a storefront approach to providing fetal scans. “We offer expectant families the opportunity to bond with their unborn child in a private & peaceful atmosphere with all the comforts of home,” says the website of Baby’s Premiere 3D/4D Ultrasound Studio LLC in New Jersey. The company didn’t respond to inquiries.

In its December warning against such “keepsake” or “entertainment” ultrasound providers, the FDA advised women to undergo the procedure only for medical reasons.

Milena Mrosovsky, 32, of Forest Hills, N.Y., estimates she underwent a dozen fetal ultrasounds when she was pregnant with her son, who is now a healthy 2-year-old. PHOTO: DOROTHY HONG FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Research suggests multiple scans don’t provide better outcomes in pregnancies. A study in the journal Lancet in 1993 set out to prove the superiority of five fetal ultrasounds over one, but it found no benefit to additional scans. “Routine scans do not seem to be associated with reductions in adverse outcomes for babies,” concluded a 2010 analysis of published literature on fetal ultrasound, by the medical-research nonprofit Cochrane Collaboration.

And fetal ultrasound sometimes produces false positives, requiring additional scans to rule out problems that never existed. The 2012 American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology paper found women who received a fetal-weight estimate via ultrasound within a month of delivery were 44% more likely to be delivered by caesarean section.

“If you go looking for trouble,” Duke’s Dr. Kuller says of unnecessary scans, “you will find it.”

The big unknown that concerns many experts who argue for minimal ultrasound use: the effect of the modern procedure’s high power.

Acoustic waves in fetal ultrasounds were much weaker when, before the mid-1990s, several large epidemiologic studies found no health differences between children exposed in utero to ultrasound and those not exposed.

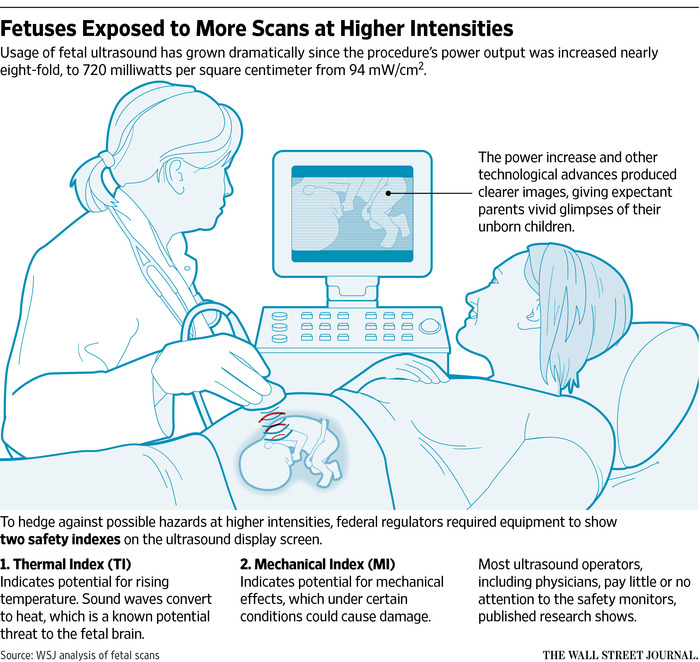

Then a consortium of physicians and manufacturers persuaded the FDA to raise power limits—in part because, under previous constraints, the obesity epidemic was making it difficult to gain clear images of some fetuses. Obstetricians also argued that clearer images would enable more-accurate findings from the procedure.

In 1992, the FDA raised the allowable fetal-ultrasound output to 720 milliwatts per square centimeter—a measurement of acoustic energy and intensity—from the previous 94.

Since then, no large epidemiologic studies have been performed on the safety of fetal ultrasound. “No epidemiological or other evidence was then [in 1992], or is now, available to support the assertion of safety at these higher exposures,” said a 2012 British Institute of Radiology book, “The Safe Use of Ultrasound in Medical Diagnosis.”

That book found that the benefits of fetal ultrasound outweigh potential risks if the procedure is used cautiously.

Recent research raises questions about how cautiously the procedure is being performed. When the FDA raised power limits, it required equipment to display two safety indexes. A thermal index, or TI, indicates potential for rising temperature. A mechanical index, or MI, indicates the potential for mechanical effects that could pose risks to tissue and cells.

Most fetal-ultrasound operators pay little attention to the TI or MI, according to at least four studies published since 2008. A study published this spring found that it didn’t help to give operators a “reference tool” informing them how to use the indexes: “Operators in this research study exhibited little knowledge about the TI or MI, and these findings are similar to previous studies on the topic,” concluded the article in the Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography.

The American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine’s newly elected president, Harvard obstetrics professor Beryl Benacerraf, says one of her goals is to increase the quality of fetal-ultrasound training so that the indexes aren’t ignored. “We’re trying to rectify that,” she says.

Some neuroscientists have been subjecting fetal animals to ultrasound. A 2006 Yale University study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found neurological abnormalities in mice exposed to ultrasound in utero. A 2009 study by Australian researchers in the International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience found fetal chicks exposed in eggs to ultrasound demonstrated post-birth learning and memory deficits.

A University of Washington study published last year in the journal Autism Research found that mice exposed to ultrasound in utero exhibited hyperactivity and social deficits in the presence of other mice.

In a study funded by the National Institutes of Health, Yale neurobiology chief Dr. Pasko Rakic is subjecting fetal primates to ultrasound to examine their brains post-birth for possible neurological abnormalities.

Obstetricians such as Frank A. Chervenak, chairman of obstetrics at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/ Weill Cornell Medical Center, believe further research will prove fetal ultrasound harmless.

But usage should be once or twice, absent medical reasons for additional scans, Dr. Chervenak says, “on the chance that there is some unknown association.”

—Rob Barry contributed to this article.

Write to Kevin Helliker at kevin.helliker@wsj.com