Cytotec/Misoprostol Obstetrics and Gynaecology

Birth

trauma

INDUCTION WITH CYTOTEC/MISOPROSTOL IS KILLING WOMEN AND

BABIES

Jeanice Barcelo

SUNDAY, MARCH 3, 2013

http://birthofanewearth.blogspot.co.uk

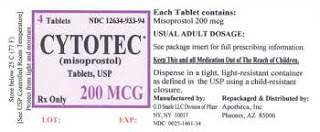

Cytotec/Misoprostol is a ulcer drug. Despite the fact that the makers of this

drug have warnings on the label saying the drug should not be used during

pregnancy, it is nevertheless being used off-label in hospitals every day to

induce labor and force babies to come before they are ready. It is an extremely

dangerous drug and is killing women and babies.

"...misoprostol is associated with an increase in meconium staining, uterine

hyperstimulation, uterine rupture, amniotic fluid embolism, maternal mortality,

perinatal mortality and hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy of surviving infants....

Although hard data cannot be found on the number of uterine ruptures following

misoprostol induction in the United States, an Internet organisation has

identified over 380 women who have had uterine rupture, many following

misoprostol30 and there is considerable anecdotal evidence that many babies

died...

a number of law suits have alleged that negligent induction of labour with

misoprostol has damaged the baby and/or the mother. There are no known

systematic data on cases of litigation associated with misoprostol induction but

at least 16 cases have been reported,22 and all suits known to have been

resolved to date have been settled in favour of the plaintiff...

Full article here:

"Drugs are licensed to treat specific conditions but

doctors can use them for other reasons so long as they take responsibility. This

is called ‘off-label’ use. Sometimes the drug has not been submitted to the

regulatory system for the indication, other assessment has revealed that use for

this indication is contraindicated. Such ‘contraindicated’ use is probably a

greater risk than ‘off-label’.

Doctors use drugs off-label if they are convinced their patient cannot wait for

regulatory approval, there is no other available licensed drug, if they judge

that the benefits outweigh the risks or sometimes just because the unlicensed

drug is cheaper.1 The practice is common in obstetrics. In one survey2 of 731

birthing women, 23% had received off-label drugs. Such prescribing is rarely

controversial. Of the 10 off-label drugs in the survey, only one, the use of

misoprostol for labour induction, the subject of this commentary, carries

serious risks.

Misoprostol (prostaglandin E1) is marketed as Cytotec for the oral treatment of

peptic ulcers. It has uterotonic activity but is not only unlicensed for use in

pregnancy but labelled as contraindicated in pregnant women. Nevertheless, it

has been used for the induction of labour since the 1990s.

This off-label use is unusual, in that other related products such as

dinoprostone (prostaglandin E2) and oxytocin are licensed for labour induction.

It was also potentially hazardous because early prescribers did not know the

correct dose or the suitability of the oral formulation for vaginal use. The

research they conducted to find out was relatively haphazard, and few patients

were informed that they were receiving an unlicensed drug.

Indirect evidence suggests that many American women have been given misoprostol

for labour induction. Induction of labour was used in 18% of births in 19983

approximately 720,000 inductions annually and in at least two large US

hospitals,4 it was the most common agent used. It has been described in the

media as ‘the drug of choice for induction of labour’.5 It has also been widely

used to induce labour in women with a previous caesarean section.6 In Portland,

Oregon it was used in 60% of patients with previous caesarean deliveries who

underwent induction of labour between 1996 and1998.4

Prelicensing studies normally consist of randomised trials performed to the

standards of the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical

Practice (ICHGCP).7 This never happened with misoprostol for labour induction.

Instead, doctors experimented with the dosage, either by informally ‘trying out’

the drug or performing small trials with idiosyncratic research protocols,

eventually accumulating sufficient data to assess efficacy. The tablets came in

unscored 100 μg and scored 200 μg tablets, so clinicians first tried one 100 μg

tablet every 4 to 6 hours, either orally or vaginally. When uterine

hyperstimulation and the occasional uterine rupture occurred, the dose was

reduced by cutting the 100 μg tablets into halves or quarters, and by 2001, the

consensus was for 25 μg (1/4 tablet) given vaginally every 4 to 6 hours.8 Even

now some hospital pharmacies decline to cut unscored tablets due to the inherent

inaccuracy of dose.

Vaginal pessaries are normally formulated differently to oral tablets. They are

shaped for ease of insertion and use different excipients including different

binders, fillers, lubricants, disintegrants. Using an oral tablet vaginally

results in a different pharmacological effect. Vaginal application of

misoprostol results in slower increases and lower peak plasma concentrations

than oral, but overall drug exposure is increased.8 With vaginal insertion, the

plasma concentration remains near peak levels 4 hours after insertion.9

Researchers also compared misoprostol with oxytocin,10 with dinoprostone

(prostaglandin E2) gel11–13 and dinoprostone vaginal inserts,14–16 as well as

oral and vaginal use.17–19 However, no trial was of sufficient size to measure

or compare reported rare but serious risks such as uterine rupture, amniotic

fluid embolism or neonatal and maternal mortality.4,6,10–15,17,18,20

Despite the fact that off-label users may be less inclined to report adverse

effects to the authorities, preliminary data suggest that misoprostol is

associated with an increase in meconium staining, uterine hyperstimulation,

uterine rupture, amniotic fluid embolism, maternal mortality, perinatal

mortality and hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy of surviving

infants.4,6,8,10–16,19–27 There are many other examples of tragedies following

the widespread use of procedures or drugs before adequate scientific evaluation,

such as routine prenatal X-ray pelvimetry, di-ethylstilboesterol and thalidomide

during pregnancy.

Small trials and lack of standardisation of research protocols has made

meta-analysis unreliable.25 The editor of this journal, commenting on a

misoprostol induction trial in January 2004 wrote: ‘Previous trials have been

too small to provide clear evidence on rare but important outcomes such as

uterine rupture, and even in the present larger trial there was only one uterine

rupture in each group’.27 One review admits: ‘the relative risk of rare adverse

outcomes with the use of misoprostol for induction of labour remains unknown’.8

and the latest Cochrane review laments that ‘The studies reviewed were not large

enough to exclude the possibility of rare but serious adverse events,

particularly uterine rupture, which has been reported anecdotally following

misoprostol use in women with and without previous caesarean section’.21

The situation with misoprostol induction after caesarean is complicated by the

fact that other prostaglandins are not licensed either, so the extent to which

complications such as uterine rupture result from misoprostol itself or from the

use of prostaglandin in general remains unclear.8 Two articles suggest a higher

risk of uterine rupture with misoprostol induction than for the other

prostaglandins.4,6

Normally, patients given an experimental drug, whether in a formal trial or in

an uncontrolled way, are fully informed and given written consent. However,

patients prescribed off-label are rarely told, and the American College of

Obstetrics and Gynecology has said that informing patients is up to the

discretion of the clinician.28 Many patients appear to have been just told that

it was ‘safe’. The patient information sheet at one UK hospital stated in 2003

(Sheila Kitzinger, personal communication): ‘Many pregnant women world-wide have

used misoprostol for labour and shown it to be safe for you and the baby’.29

Among 16 patients experiencing adverse outcomes after misoprostol induction in

the United States,22 none had been informed that it was not approved although

they had been told it was ‘safe’. In interviews on national television, women

with uterine rupture after misoprostol induction have claimed to have not been

informed that the drug use was off-label.5

The lack of informed consent matters. Although hard data cannot be found on the

number of uterine ruptures following misoprostol induction in the United States,

an Internet organisation has identified over 380 women who have had uterine

rupture, many following misoprostol30 and there is considerable anecdotal

evidence that many babies died.4,6,8,16,19,21–24 In a case–control study of

uterine rupture in 512 women attempting vaginal birth after caesarean section,4

5.6% of the women in the misoprostol group had symptomatic uterine rupture, as

compared with 0.2% of the women undergoing a trial of labour without the

administration of misoprostol (P < 0.001).8 At least four women have died after

misoprostol induction of labour, all with postmortem findings consistent with

amniotic fluid embolism.20,22–24 To date, published trials are too small to

calculate the rate of uterine rupture and the rate of amniotic fluid embolism in

labours induced with misoprostol on an unscarred uterus, although a warning of

both risks is included in the package insert and in a letter from the

manufacturer Searle to doctors.26 Perhaps unsurprisingly, a number of law suits

have alleged that negligent induction of labour with misoprostol has damaged the

baby and/or the mother. There are no known systematic data on cases of

litigation associated with misoprostol induction but at least 16 cases have been

reported,22 and all suits known to have been resolved to date have been settled

in favour of the plaintiff. In late 1999, the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists came out against misoprostol use with a scarred uterus but not

against its use for induction on an intact uterus. In 2000, Searle, the

manufacturer of Cytotec, at the request of and in close collaboration with the

FDA,26 wrote to all American physicians reminding them that using it for labour

induction was contraindicated, listing the adverse effects reported to them and

the FDA and urging them not to use it for labour induction. Most other expert

committees including those of the British Royal College31 and the Canadian

Society32 have concluded we do not yet know enough about the risks of

misoprostol induction to use it, except in approved experimental trials with

fully informed consent."

Source Article

Off-label use of misoprostol in obstetrics: a cautionary tale

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00445.x/full