"They are almost frightening-looking young men," she continues, "even more modern than modern. The funny thing is that when they smile - not often - they look perfectly wholesome and nice. But the rest of the time they look wicked and dreadful and distinctly evil, in an 18th-century sort of way. You almost expect them to leap out of pictures and chant magic spells."

Published three weeks after Maureen Cleave's ground-breaking piece in London's Evening Standard ("Why the Beatles Create All That Frenzy"), the Boyfriend article ("Pop A La Mod") was one of the first in-depth articles about the group. It was well-written, informative on their backstory, and makes it clear just how weird the Beatles were when they first arrived.

As a magazine aimed at young women, with colour pin-ups, ads for cosmetics and hair lacquer, and plentiful picture stories ("The Model Bride: a career-girl or a happily married bride? The girl in our story had to choose"), Boyfriend picked up on the hysteria surrounding the Beatles and invested heavily in the British pop boom that they helped to create.

In summer 1963 the magazine produced "Big New Beat", the first of several pop supplements "about the Northern Raves". The Beatles were on the cover, standing amid the rubble of Euston Road. Inside were group shots and candid close-ups with large type comments: "They have a knack of looking as if they'd just landed on this planet. They're otherworldly, that's what they are."

The photographs were taken in April 1963 by Fiona Adams, a Boyfriend regular: one shot from the session was used by EMI for the front cover of the Beatles' Twist and Shout EP, which, released in July 1963, sold so many that it made No 4 in the singles charts. Showing the group leaping into the air with sheer joie de vivre, it remains one of the key 60s images.

A new show at the National Gallery, Beatles to Bowie: the 60s Exposed, contains Fiona Adams's contact sheets from that day, along with dozens of other photographs that have not been seen since their first publication in the music and young women's magazines of the 60s. This is a previously unreckoned resource uncovered by curator Terence Pepper: a treasure trove of words and pictures.

During the high pop 60s, between 1963 and early 1967, Britain had an incredibly vigorous pop and teen press, with at least a dozen weeklies and/or monthlies vying to bring their readers all the latest news, gossip and interviews about the Beatles, the Stones, the Searchers, Cilla and Dusty, right the way through to the Walker Brothers and the Small Faces.

Selling between 70,000 or so copies (Record Mirror) up to 200,000 (Fabulous, the New Musical Express) a week, their total circulations combined to several hundred thousand. This paralleled the unprecedented spike in singles sales in the years after the Beatles' breakthrough: reaching a peak of more than 70m in 1964.

These magazines created an all-inclusive, almost hermetically sealed environment of Super Pop. Things were changing so fast that they were put together without much reflection or much heed of the morrow. Reading them today, they are both time-locked and immediate: they are historical documents yet retain the fervour of the moment.

This exponential growth was based on sound demographics. In his influential 1959 pamphlet, The Teenage Consumer, Mark Abrams observed that teenagers comprised 13% of the UK population. This figure rose as the postwar baby boom worked its way through - reaching its first peaks in 1960, 1962 and 1963 when the 10-19 age group rose to nearly 15% of the total.

During the late 1950s, the American consumer society spread throughout Britain. In an era of plentiful jobs, British teenagers had double the spending power that they had in 1939. Temporarily free of responsibilities, they bought a wide range of items: cosmetics, magazines, clothes, soft drinks, cinema tickets, and - most of all - records and record players (44% of the UK total).

By the early 1960s, there were already several weeklies catering to the teenage female market - long established as being in the forefront of youth consumerism - by publishers including Fleetway, George Newnes and C Arthur Pearson: Marilyn, Mirabelle, Romeo, Roxy, and Valentine. Boyfriend was launched in 1959, with Marty - based on the popularity of Marty Wilde - following in 1960.

The newer titles were more pop-heavy: as well as "love scene" picture stories and problem pages, there were innovative layouts and colour photos. The star staples were Elvis, Cliff Richard, Adam Faith, John Leyton, Eden Kane: the Tin Pan Alley-manufactured dream teen pop of the early 60s was perfect for the girls' mags, leaving the weekly music papers somewhat becalmed.

Of these, there were several. Launched in 1926, Melody Maker was the longest-running: with its particular commitment to jazz, folk and blues, it was not pure pop. That slack was taken up by the New Musical Express (est 1952), Record and Show Mirror (est 1953 as Record Mirror) and Disc (est 1958). All were monochrome, with weekly charts and plenty of news: aimed at young men as well as women.

Basically you paid your money and you made your choice. Melody Maker was serious about music: jazzcentric, it made headway during the ghastly early 60s trad boom. The New Musical Express was hamstrung by its prominent front cover ad, but it had great insider gossip: "Tail-Pieces by the Alley Cat". Disc was poppier, with prominent charts and front-page news stories.

The Beatles' arrival revolutionised pop publishing. Boyfriend's Big Beat No 2 (autumn '63) promised "12 colour pages and all the mod pop that's popping". Inside were Cliff and Elvis but coming up fast vying were the Searchers ("1864 Mods"), Freddie and the Dreamers ("it's rough tough and jumping music") and "those strange boys from south London", the Rolling Stones.

Two important new weeklies were launched in January 1964. Jackie ("for go-ahead teens") was published by DC Thomson as a girls' "comic", a streamlined version of Boyfriend: all the same elements but with larger pages and unusual, candid shots of stars like the Beatles. It was a winning mixture: by the late 60s, its circulation was up to half a million.

Fabulous (Fleetway) was a completely new tabloid pop paper. Predicated on "Merseymania", it contained at least one pin-up of the Beatles in every issue for two years. Several issues, like that of 15 February 1964, were almost totally devoted to the group, with quirky features, 11 colour pages, and a central double-page poster (now hard to find, as they were usually stuck on the wall).

Selling for one shilling, Fabulous was pricier than the competition but it had more pages, better quality paper, and a regular team of photographers such as Fiona Adams, Bill Francis and David Steen. It had self-promoting transfers, black American faces (Martha and the Vandellas) and theme issues, like the "Gets the Vote" edition that coincided with the October 1964 general election.

It also introduced a more direct rapport between the stars and their keenly attuned audience. In the all-Beatles 15 February 1964 edition, there were articles about "famous escapes" (how the Beatles got away from the fans after a show), Brian Epstein speaking in his own words, and a forensic breakdown of Paul, Ringo, George and John's height, weight, eye colour, inside leg etc.

Features showing stars in their own homes were interspersed with old school photos and pop stars' musings on ideal girls. At the same time, Fabulous had guest editors: for the 14 August 1965 issue, "those gorgeous" Kinks took over, making space for the Animals, Goldie and the Gingerbreads, Manfred Mann and - oddly enough, bearing in mind their spiky relationship - the Who.

Fabulous saw pop not just as a teen process but as part of something wider. Fashion was given prominent space, not only in the adverts, but in spreads directly related to star "gear". A double page spread on "bee-oootiful beat babes" showed the Beatles in their corduroy jackets and then told you where to buy them - cut for the young female shape of course.

After the Beatles cracked America, British pop culture entered a new phase: it was clear that this was not parochial, not Tin Pan Alley, not about to disappear into variety and lame musicals. Pop was not only yoked to a generational assertion of power ("Ringo for PM") but the global re-branding of a static, class-bound country in terms of novelty, speed and creativity.

Britain became Pop Island and the bombsite-ridden capital a youth mecca. On 3 October 1964, Fabulous published its "Shaking London Town" issue, with a spread about the best TV programme of the day, Ready Steady Go!, as well as Vicki Wickham's "POP guide to London", which featured hairdressing salons, recording studios, clubs, mod shops, and the Fabulous offices themselves.

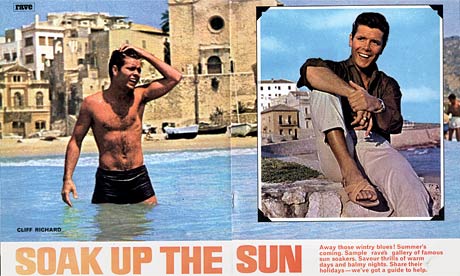

This widescreen view of pop culture was also assumed in another great magazine launched in early 1964. At 2s 6d, Rave (George Newnes) was five times as expensive as the weekly music papers, but in return you got an 80-page or so A4-size monthly, with excellent quality paper, meaty content and great photographs - by Jean Marie Perier, Terry O'Neill, Marc Sharratt and others.

The first issue showed the cross-media spread of British pop culture with a front cover shot of the Beatles with 007 badges. Paul McCartney has a spy camera, while Ringo's gun shoots BANG. Inside are Dusty's fashion tips, a feature on star holidays (Sitges, Corfu etc) and a regular monthly event, DJ Alan Freeman's "Heart to Heart": this month, Billy Fury - '"The Billy No One Knows".

Rave went further and deeper with articles about Stuart Sutcliffe, the lost Beatle, a fashion round table with John Stephen and the Pretty Things, and notices about up-and-coming groups such as the Yardbirds. Photo shoots were set in (for then) unusual locations, like Portobello Road or Covent Garden, and stars including Jeff Beck were used to model gear such as PVC overcoats.

Like Fabulous, Rave prominently featured young women writers. Cathy McGowan was a regular, along with Maureen O'Grady and Dawn James. However, if the ads for guitars were anything to go by, Rave also appealed to young men. Balancing teen pop with groups like the Yardbirds, the Byrds and the Who, it acquired a circulation of 125,000 by 1966.

The music weeklies responded to this challenge by consolidating and hiring new writers. Disc sharpened up its act with bang-up-to-the-minute news stories on the front page, race-track-style chart rundowns ("Kinks Hit Crisis" at No 4), a contentious readers' postbag ("How dare Crispian St Peters Knock the Beatles!") and incisive singles reviews by the great Penny Valentine.

Melody Maker developed a good line in eye-catching headlines ("Dylan Digs Donovan!" from 8 May 1965) and increased its circulation to nearly 100,000. Record Mirror also had colour and was well-regarded for its thorough charts page, James Hamilton's comprehensive singles reviews, and Tony Hall's inspired column. On the back page was a gossip column, called "The Face".

Despite the formulaic banality of Derek Johnson's singles reviews ("a rock ballad with a plaintive, throbbing beat"), the New Musical Express was still the brand leader, peaking at over 300,000 in 1965. A sample issue from that year (26 March) has Keith Altham tackling "A Kink A Week", Sue Mautner visiting "Brian Jones's New Pad" and pictures from the Ready Steady Go! Tamla TV spectacular.

1966 was the year of change. Singles' sales dropped by 10m. The papers began to feature stories about star exhaustion and unavailability: the surliness of the Kinks, the Who and the Rolling Stones. A new micro-generation of more cheerful groups appeared, apparently unburdened by significance: the Troggs, Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich, the Monkees.

The unitary motion of the high 60s was beginning to falter. Sentimental "mums and dads" ballads returned with a vengeance, Soul engaged the hardcore mods, while the drug culture began to take an effect. Rave was particularly hostile to the last development and vainly predicted, in its January 1967 issue, that "psychedelic music and psychedelic happenings won't happen".

Pop was hoist on the petard of its own success. Having become a big business, it was doing what all big businesses do: diversifying rapidly. The problem for editors was basic: how to keep the readership going with a narrative thread that jumped from the Walker Brothers to Engelbert Humperdinck, the Jimi Hendrix Experience and all points in between.

It was time for another change. During 1966, Fabulous became Fabulous 208; Boyfriend merged with the newly launched Petticoat, Marilyn with Valentine. Disc joined forces with Music Echo (which had already taken over Bill Harry's Mersey Beat) and went colour on the front and back pages. Albert Hand's small-sized glossy, Pop Weekly, stopped publication.

There were new countercultural magazines. Some of these were short-lived (Cue, Intro) but others - such as Oz and Rolling Stone - were better suited to a market where long-players outsold singles, which they did from 1968 onwards. A revamped New Musical Express followed suit. Pop chatter became rock writing, with all the consequent highs and lows.

The first-time freshness of the high 60s is now well over 40 years gone, but you can still read it preserved in tattered bits of ephemera: the old copies of Rave, Disc and Fabulous that still regularly surface. In them you will find forgotten photographs - like Brian Jones dressed up, for some reason, in an SS uniform - items of gossip and surprisingly sharp opinions and interviews.

It's the nearest you'll get to experiencing the 60s as they happened, which should be mandatory for any pop obsessive. And, for all the recent talk about rock writing, the 60s pop mags help to reassert an alternative canon: one where women have equal status; one where enthusiasm and sharpness win out over pomposity every time.

• Beatles to Bowie: the 60s Exposed, sponsored by BNY Mellon, is at the National Portrait Gallery from 15 Oct-24 Jan (npg.org.uk). The exhibition catalogue includes an essay by Jon Savage and is priced at £30

'So Keith Moon nicked a flag ...'

How the Observer's Colin Jones got the definitive photo of the Who

In the 60s, pop wasn't simply the preserve of the teen mags and red-tops. Among the most-forward looking broadsheets, the Observer, under David Astor's editorship, boasted critics including George Melly and later Nick Cohn, as well as film critic Penelope Gilliatt, champion of the Beatles' A Hard Day's Night.

In March 1966, the Observer Magazine published a famous story about the Who. Written by John Heilpern, it concentrated on the business brains behind the band's rise: manager Kit Lambert ("I like the blatantness of pop, the speed, the urgency") and his partner, Chris Stamp. But the iconic cover was the work of photographer Colin Jones, thanks to the assistance of Keith Moon. "We were at Manchester airport," Jones now recalls, "when the editor called asking me to shoot a cover, in colour. Pete Townshend had his Union Jack jacket, so I thought a Union Jack in the background would work. Keith said: 'I know where to get one of those' - and he ran downstairs and up the hotel's flagpost and nicked the flag from there!"

The son of an east London printer, Jones trained as a dancer at the Royal Ballet School, before being seduced into life as a photojournalist. Working at the Observer, alongside colleagues including Jane Bown, he travelled the world. "I was more a fan of classical music; but when I got to know the Who, I got to like them, all right."

Caspar Llewellyn Smith

The Who: In the Beginning is at Proud Central, London WC2N, 24 September-15 November. www.proud.co.uk