A Study of the International Armament Industry

MERCHANTS OF DEATH

A Study of the International

Armament Industry

a book by H.C. ENGELBRECHT, Ph.D. 1934

FOREWORD

CHAPTER 1: CONSIDER THE ARMAMENT

MAKER

CHAPTER 2: MERCHANTS IN

SWADDLING CLOTHES

CHAPTER 3: DU PONT—PATRIOT AND

POWDER-MAKER

CHAPTER 4: AMERICAN MUSKETEERS

CHAPTER 5: SECOND-HAND DEATH

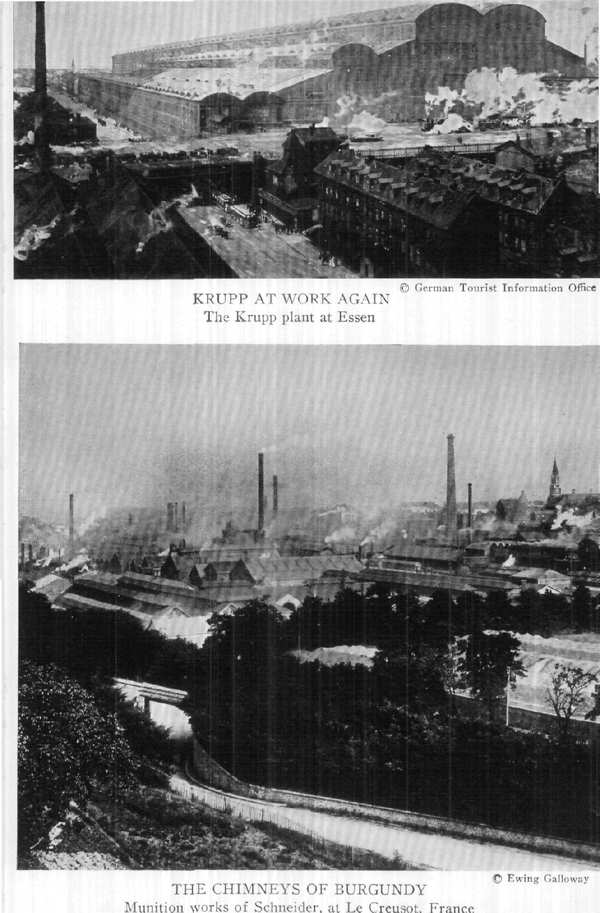

CHAPTER 6: KRUPP—THE CANNON

KING

CHAPTER

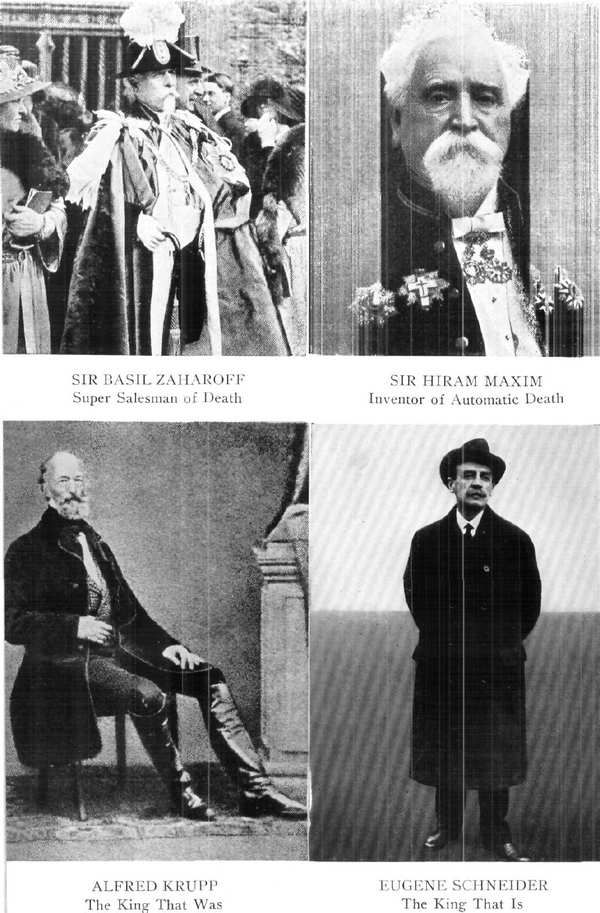

7: AUTOMATIC DEATH—THE STORY OF

MAXIM’S MACHINE GUN

CHAPTER 8: SUPER-SALESMAN OF

DEATH

CHAPTER 9: STEPMOTHER OF

PARLIAMENT

CHAPTER 10: SEIGNEUR DE

SCHNEIDER

CHAPTER 11: THE EVE OF THE

WORLD WAR—THE ARMS MERCHANTS

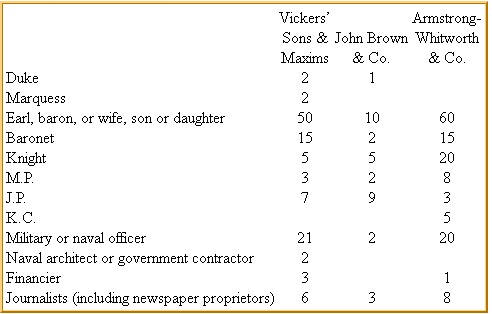

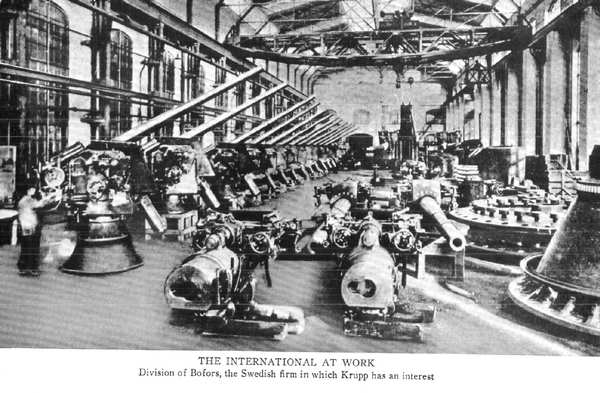

Choice of Directors

Maintaining Close Relations with Governments

Military Missions

Shares in Armament Companies

Bribery

Sabotage

CHAPTER 12: THE WORLD WAR —

THE WAR IN EUROPE

CHAPTER 13: THE WORLD WAR —

ENTER OLD GLORY

CHAPTER 15: THE MENACE OF

DISARMAMENT

CHAPTER 16: FROM KONBO TO

HOTCHKISS

CHAPTER 17: STATUS QUO

CHAPTER 18: THE OUTLOOK

Lithograph by Mabel Dwight

IT is an unmitigated pleasure for me to commend this study of the international armament industry to the civilized reading public. In several important ways this book is an outstanding contribution to the literature of history and the social sciences.

In the first place, it points out a great gap in our knowledge of a branch of technology and industry and makes a valiant beginning at filling it. The evolution of firearms has played a very important part in the destiny of modern nations. Yet, for no generation or country is there a thoroughly satisfactory monographic treatment of the evolution of the firearms industry therein. There has been no end of writing on the wars which have been fought, but little or nothing is told us about the reason why soldiers in the Spanish-American war were more effectively armed than those of General George Washington, and even less is told about the source of armament supplies in the various wars. Histories tell us that the Prussians were armed with the “needle gun” in the War of 1866, but not one history professor in a dozen could explain what the “needle gun” actually was or indicate the transition from the muzzle loading to the breech loading muskets.

In the second place, this study reveals illuminating information with respect to the organization and sales methods of a very considerable industry. The propaganda and high pressure salesmanship which has characterized contemporary business finds its prototype in the activities of armament manufacturers long before our generation.

There is no denying the importance of wars, particularly wars waged with contemporary methods of devastation. Wars may be a menace to the race, but their increasing ravages only make them more significant in at least a negative sense. If wars can no longer make any considerable constructive contribution to human life, they have become increasingly potent in their capacity to dislocate society and to destroy civilization. In his latest book, Mr. H.G. Wells has given us a vivid and appalling forecast of the horrors of the next world war. The technology of armaments controls the material sinews of war. As the effectiveness and deadliness of armaments has increased, war has become more devastating and demoralizing. Nothing could be more helpful than a systematic history of the armament industry in enabling us to understand why mankind needs to busy itself particularly today in bringing the material technique of mass murder under control if we wish to preserve the semblance of modern civilization. This is the third out standing merit of this book.

A fourth characteristic of this volume will commend itself to thoughtful readers, namely the comprehensive and complete character of the treatment given to the armament industry. Here is a satisfactory history of its development, an outline of its achievements, a delineation of the methods which have been followed by leading armament firms, an exposure of the degradation of ethics which has accompanied the efforts of the armament moguls to market their products, and an indication of the bearing of the whole historical study upon the outlook for world peace.

Not less impressive than the comprehensiveness of the work is the sane and reasonable tone which pervades the whole study. Most accounts of the armament industry have been written by men and women who possess all the fervor of the valiant crusader against war. It is no disparagement of the usefulness and courage of the ardent pacifist to point out that this crusading psychology does not always supply the best background for a sane perspective on the causes of war. When a professional pacifist cuts loose on the armament industry, he frequently gives the impression that the armament makers constitute the chief menace to peace. By thus obscuring much more powerful factors which make for war, such writers render at least an indirect disservice to the cause of peace.

Dr. Engelbrecht and Mr. Hanighen do not fall victim to this temptation. They thoroughly expose all the evils of the armament industry, but they remain at all times conscious that broader forces, such as patriotism, imperialism, nationalistic education, and capitalistic competition, play a larger part than the armament industry in keeping alive the war system.

In another respect also is their reasonableness conspicuously apparent. They expose the corruption, graft and disloyalty of the armament makers with a thoroughness sufficient to gratify the most determined pacifist. At the same time, they make no effort to portray these armament pirates, their lobbyists and salesmen, as peculiarly depraved members of the human race. They recognize that they are no more corrupt than, for instance, our own great investment bankers. If British tank-masters hastened to sell Russia tanks while their government was about to break off diplomatic relations with Russia, so did Mr. Mitchell and Mr. Wiggin sell short the stock of their own banks. If British airplane companies were ready to sell aircraft to the Hitler government, so did Mr. Sinclair and his associates make vast profits at the expense of their own stockholders.

Even in the armament industry the bankers have set the pace for chicanery. Few armament manufacturers have duplicated J.P. Morgan, Sr.’s sale of defective arms to John C. Frémont during the Civil War. When it comes to economic corruption, John T. Flynn’s book on Graft in Business presents a far more sorry record than does this present volume. Moreover, even though the armament makers have played a prominent part in encouraging wars, rebellions and border raids, they never exerted so terrible an influence upon the promotion of warfare as did our American bankers between 1914 and 1917. Through their pressure to put the United States into the War these bankers brought about results which have well nigh wrecked the contemporary world.

Armament makers and bankers alike are the victims of human cupidity. The only way in which the armament makers are at all unique is that they are engaged in an industry where the death of human beings is the logical end and objective of their activity.

The calmness and sanity everywhere evident in this book will make its message and implications all the more devastating. The authors can rarely be charged with any overstatement or exaggeration. All in all, the book is a conspicuous contribution to industrial history, contemporary ethics, international relations, and the peace movement. It is bound to have a civilizing effect upon all intelligent and fair-minded readers.

To give arms to all men who offer an honest price for them without respect of persons or principles: to aristocrats and republicans, to nihilist and Czar, to Capitalist and Socialist, to Protestant and Catholic, to burglar and policeman, to black man, white man and yellow man, to all sorts and conditions, all nationalities, all faiths, all follies, all causes, and all crimes. — Creed of Undershaft, the arms maker, in Shaw’s Major Barbara.

I appreciate the fact that the manufacturers of arms and ammunition are not standing very high in the estimation of the public generally. — Samuel S. Stone, President of Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Co.

IN 1930, as a result of the endeavors of disarmament advocates, a treaty was signed between the United States, Great Britain and Japan. While it fell far short of disarming these powers, it did agree on a joint policy of naval limitation and so prevented for a time a costly naval building competition between these countries. President Hoover submitted the treaty to the Senate for ratification. At this point an organization called the Navy League entered the picture. It raised strenuous objections to the treaty on the ground that it “jeopardized American security.” The League failed to convince the Senate, however, and the treaty was ratified.

Presumably the Navy League was a collection of individuals who distrusted international efforts to disarm and who believed that a large navy would insure the safety of the United States and of its citizens. Some might assail these conservatives for clinging to reactionary ideas, but their point of view was a recognized patriotic policy upheld in many who had no connection with the League. But what was the Navy League and who were its backers ?

Representative Claude H. Tavvener made a speech in Congress in 1916 which revealed the results of his investigations into the nature and character of the League. He cited the League’s official journal to show that eighteen men and one corporation were listed as “founders.” The corporation was the Midvale Steel Company from which the government had bought more than $20,000,000 worth of armor plate, to say nothing of other materials. Among the individual founders were Charles M. Schwab, president of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation, which makes armor plate and other war material; J.P. Morgan, of the United States Steel Corporation, which would profit heavily from large naval orders; Colonel R.M. Thompson, of the International Nickel Company, which dealt in nickel, that metal so necessary in making shells; and B.F. Tracy, former Secretary of the Navy, who became attorney for the Carnegie Steel Company. More than half of the founders of this energetic League were gentlemen whose business would benefit by large naval appropriations. It is evident from this that American arms makers have employed the Navy League to prevent naval disarmament.1

In Europe their colleagues are even more active. Hitler has now become the symbol of the return of German militarism. Even before he managed to obtain supreme power there was speculation as to his financial backers. Obviously they included German industrialists fearful of socialism, communism, and the labor unions, nationalists smarting under the “insults” of the Versailles treaty, and a host of other discontented folk. But on the list of these contributors supplying funds to the Hitler movement were the names of two capitalists—Von Arthaber and Von Duschnitz—directors of Skoda, the great armament firm of Germany’s neighbor and enemy, Czechoslovakia.

Interlocking directorates are a familiar phenomenon in the United States. The real controller of industries is frequently found in the most unexpected places. In Europe the same system prevails. And so it appears that Messrs. Von Arthaber and Von Duschnitz represent a firm which is controlled by still another firm. The head of this holding company is neither German nor Czech. He is a French citizen, M. Eugene Schneider, president of the Schneider-Creusot Company which for a century has dominated the French arms industry and which through its subsidiaries now controls most of the important arms factories in Central Europe. Some of Hitler’s financial support, then, was derived from a company owned by a leading French industrialist and arms maker.2

Arms merchants also own newspapers and mold public opinion. M. Schneider is more than just president of Creusot. He is the moving spirit of another great combine, the Comité des Forges. This French steel trust through one of its officers has controlling shares in the Paris newspaper Le Temps, the counterpart of The New York Times, and the Journal des Débats, which corresponds to the New York Herald Tribune. These two powerful papers constantly warn their readers of the “danger of disarmament” and of the menace of Germany. Thus M. Schneider is in a position to pull two strings, one linked to Hitler and German militarism, the other tied to the French press and French militarism.3

Arms merchants have long carried on a profitable business arming the potential enemies of their own country. In England today in Bedford Paale there is a cannon captured by the British from the Germans during the World War. It bears a British trademark, for it was sold to Germany by a British firm before the war. English companies also sold mines to the Turks by which British men-of-war were sunk in the Dardanelles during the war. The examples of this international trade in arms before the war are legion, as will be shown.4

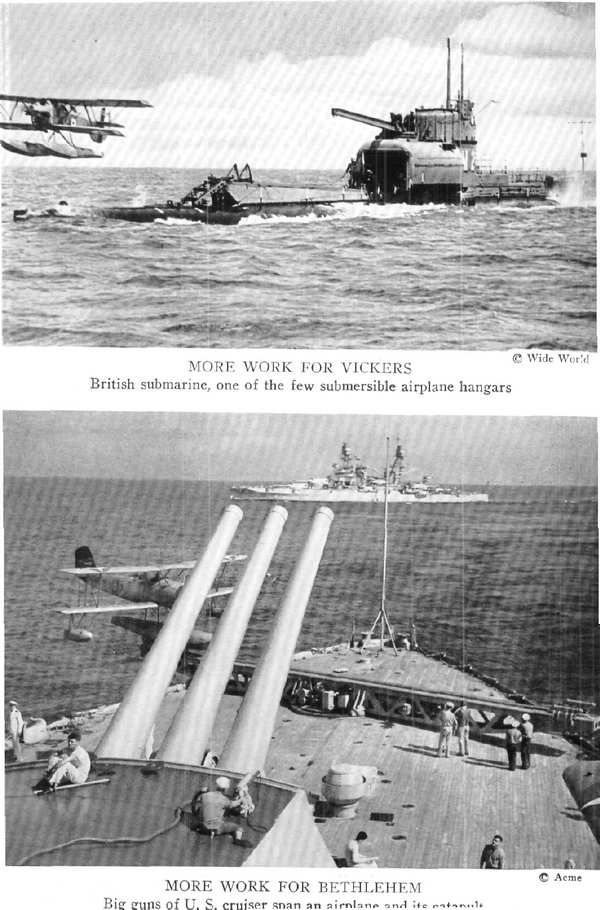

Nor are they lacking today. Recently the trial of the British engineers in Soviet Russia brought up the name of Vickers, the engineering firm which employed the accused. But Vickers has other lines than building dams for Bolsheviks. It is the largest armament trust in Great Britain. For years relations between the Soviets and Great Britain were such that the Soviets were convinced that Britain would lead the attack of the “capitalist powers” on Russia. Yet in 1930 Vickers sold 60 of its latest and most powerful tanks to the Soviets.5

Today Russia is less of a problem to England than is Germany. The rise of Hitler has reawakened much of the pre-war British suspicion of Germany. Germany was forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles to have a military air force. Yet in1933, at a time when relations between the two countries were strained, the Germans placed an order with an English aircraft manufacturer for 60of the most efficient fighting planes on the market, and the order would have been filled had not the British Air Ministry intervened and refused to permit the British manufacturer to supply the planes.6

Arms makers engineer “war scares.” They excite governments and peoples to fear their neighbors and rivals, so that they may sell more armaments. This is an old practice worked often in Europe before the World War and still in use. Bribery is frequently closely associated with war scares. Both are well-illustrated in the Seletzki scandal in Rumania. Bruno Seletzki (or Zelevski) was the Skoda agent in Rumania. In March, 1933, the Rumanian authorities discovered that this Czech firm had evaded taxes to the extent of 65 million lei. In searching Seletzki’s files, secret military documents were found which pointed to espionage. The files were sealed and Seletzki’s affairs were to undergo a thorough “airing.”

A few days later the seals were found broken and many documents were missing. Seletzki was now held for trial and his files were carefully examined. The findings at that time pointed to widespread corruption of important government and army officials. Sums amounting to more than a billion lei had been distributed among the “right” officials, hundreds of thousands had been given to “charity” or spent on “entertainment,” because the persons receiving these sums “will be used by us some day.” The war scare of 1930was revealed as a device to secure Rumanian armament orders, for Russia at that time was represented as ready to invade Bessarabia, and Rumania was pictured as helpless against this threat; all the hysteria vanished over night when Skoda was given large armament orders by the Rumanian government. General Popescu who was involved shot himself in his study and other officials were exceedingly nervous about the revelations which might yet come. It was never revealed who Seletzki’s friends in the Rumanian government had been.7

All these incidents took place in times of peace. Presumably arms merchants become strictly patriotic once their countries start warlike operations. Not at all ! During the World War at one time there were two trials going on in France. In one, Bolo Pasha was facing charges of trying to corrupt French newspapers in the interest of the Central Powers. He was convicted and executed. In the other, a group of French industrialists were tried for selling war material to Germany through Switzerland. Although the facts were proved, these industrialists were released because they had also supplied the French armies. This is but one of a number of sensational instances of trading with the enemy during the war.8

Dealers in arms are scrupulously careful in keeping their accounts collected. Previous to the World War, Krupp had invented a special fuse for hand grenades. The English company, Vickers, appropriated this invention during the war and many Germans were killed by British grenades equipped with this fuse. When the war was over, Krupp sued Vickers for violation of patent rights, demanding the payment of one shilling per fuse. The total claimed by Krupp was 123,000,000 shillings. The case was settled out of court and Krupp received payment in stock of one of Vickers’s subsidiaries in Spain.9

Reading such accounts many people are shocked. They picture a group of unscrupulous villains who are using every device to profit from human suffering and death. They conjure up a picture of a well-organized, ruthless conspiracy to block world peace and to promote war. Theirs is an ethical reaction easily understood. For the business of placing all our vaunted science and engineering in the service of Mars and marketing armaments by the most unrestricted methods of modern salesmanship is indeed a thoroughly anti-social occupation.

But the arms merchant does not see himself as a villain, according to his lights he is simply a businessman who sells is wares under prevailing business practices. The uses to which his products are put and the results of his traffic are apparently no concern of his, no more than they are, for instance, of an automobile salesman. Thus there are many naive statements of arms makers which show their complete indifference about anything related to their industry save financial success. One British arms manufacturer, for instance, compared his enterprise to that of a house-furnishing company which went so far as to encourage matrimony to stimulate more purchases of house furnishings. The arms maker felt that he, too, was justified in promoting his own particular brand of business.

Neither of these two points of view the average man’s accusation and the arms maker’s defense- is an adequate statement of the issues involved. One may be horrified by the activities of an industry which thrives on the greatest of human curses; still it is well to acknowledge that the arms industry did not create the war system. On the contrary, the war system created the arms industry. And our civilization which, however reluctantly, recognizes war as the final arbiter in international disputes, is also responsible for the existence of the arms maker.

Who, to be specific, has the power to declare war ? All constitutions in the world (except the Spanish) vest the war-making power in the government or in the representatives of the people. They further grant the power to conscript man-power to carry on such conflicts. Why is there no ethical revolt against these constitutions ? Governments also harbor and foster forces like nationalism and chauvinism, economic rivalry and exploiting capitalism, territorial imperialism and militarism. Which is the most potent for war, these elements or the arms industry ? The arms industry is undeniably a menace to peace, but it is an industry to which our present civilization clings and for which it is responsible.

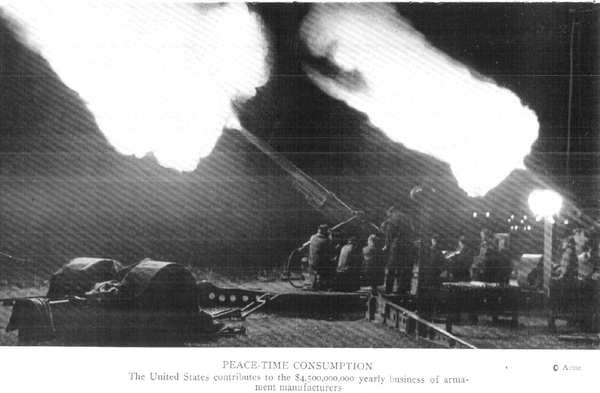

It is an evidence of the superficiality of many peace advocates that they should denounce the arms industry and accept the present state of civilization which fosters it Governments today spend approximately four and a half billion dollars every year to maintain their war machines. This colossal sum is voted every year by representatives of the people. There are, of course, some protests against these enormous military outlays and a handful of individuals carry their protest so far as to refuse to render military service and to pay taxes. But by and large it is believed that “national security” demands these huge appropriations. The root of the trouble, therefore, goes far deeper than the arms industry. It lies in the prevailing temper of peoples toward nationalism, militarism, and war, in the civilization which forms this temper and prevents any drastic and radical change. Only when this underlying basis of the war system is altered, will war and its concomitant, the arms industry, pass out of existence.

While critics of the arms makers are thus frequently lacking in a thorough understanding of the problems involved, the apologists of the arms makers, who defend the purely commercial and nonpolitical nature of the traffic in arms, are far from profound. The fact is that the armament maker is the right-hand man of all war and navy departments, and, as such, he is a supremely important political figure. His sales to his home government are political acts, as much as, perhaps even more so, than the transactions of a tax collector. His international traffic is an act of international politics and is so recognized in solemn international treaties. The reason this aspect has never been emphasized is that most nations are extremely anxious to continue the free and uninterrupted commerce in armaments, because they do not and cannot manufacture the arms they deem necessary for their national safety. From this the curious paradox arises that an embargo on arms is everywhere considered an act of international politics, while the international sale of arms, even in war time, is merely business.

This is the complex situation which breeds such a singular intellectual confusion. The world at present apparently wants both the war system and peace; it believes that “national safety” lies in preparedness, and it denounces the arms industry. This is not merely confused thinking, but a striking reflection of the contradictory forces at work in our social and political life. Thus it happens that so-called friends of peace frequently uphold the institution of armies and navies to preserve “national security,” support “defensive wars,” and advocate military training in colleges. On the other hand, arms makers sometimes make dramatic gestures for peace. Nobel, the Dynamite King, established the world’s most famous peace prize; Andrew Carnegie endowed a peace foundation and wrote pamphlets on the danger of armaments; Charles Schwab declared that he would gladly scrap all his armor plants if it would bring peace to the world; and Du Pont recently informed its stockholders that it was gratified that the world was rebelling against war.

Out of this background of conflicting forces the arms-maker has risen and grown powerful, until today he is one of the most dangerous factors in world affairs — a hindrance to peace, a promoter of war. He has reached this position not through any deliberate plotting or planning of his own, but simply as a result of the historic forces of the nineteenth century. Granting the nineteenth century with its amazing development of science and invention, its industrial and commercial evolution, its concentration of economic wealth, its close international ties, its spread and intensification of nationalism, its international political conflicts, the modern armament maker with all his evils was inevitable. If the arms industry is a cancer on the body of modern civilization, it is not an extraneous growth; it is the result of the unhealthy condition of the body itself.

This book presents the outline of the development of this powerful industry-not its history, for that may never be fully written. Hidden in government archives are doubtless many documents which would modify or alter some of the statements herein made. Others, safely protected in the files of the various arms companies—or perhaps destroyed because they were incriminating—may never reach the public. Powerful and mysterious arms salesmen like Sir Basil Zaharoff may die without ever telling the true tale of their achievements. But there are enough unguarded announcements, legislative investigations, court trials, company histories, and boasts of successful arms dealers in their own official publicity to trace the growth of this industry.

It is a long story, with its curious birth, uncertain adolescence, confident maturity, and promise of greater vitality; on the other hand there are elements of decay and serious threats to its continued existence. It has had its great figures, its demigods, staunch adherents of its old code, pioneers of the new. It came into existence back in the Middle Ages when the arquebuse was anew and fearful weapon; it crossed the path of the great Napoleon; Thomas Jefferson had close personal relations with one of its intrepid pioneers; it was so intimately bound up with the Crimean War that a certain poem should read:

International cannon to right of them,The Kaiser was defied by one of its heroes, “King” Krupp; the proud British empire was scared to death in 1909 by a smart little arms promoter from Leeds; and only yesterday one of its champions put over a most “patriotic” deal at Geneva. It is a past replete with extraordinary episodes, projecting an ominous shadow into the future.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 Charles A. Beard, The Navy, Defence or Portent ? pp. 156-184.

2 Paul Faure, Les Marchands de Canons contre la Paix.

3 The Secret International, p. 22.

4 Parliamentary Debates, August 2, 1926.

5 Lehmann-Russbueldt, Die Revolution des Friedens, p. 26.

6 New York Times, July 5, 1933.

7 Union of Democratic Control, Patriotism, Ltd., pp. 24-30; Reber, “ Puissance de la Skoda et son Trust,” Le Monde, No. 255, April 22, 1933.

8 Francis Delaisi, “ Corruption in Armaments,” Living Age, September, 1931, p. 56.

9 Lehmann-Russbueldt, War for Profits, p. 131.

IT all began in the “ Middle Ages ” with the importation of gunpowder into Europe. Kings had just learned how to employ crossbows against rebellious nobles. With small companies of accurate bowmen they were able to chase the armoured knights off the field of battle and into the shelter of baronial castles. But arrows were feeble missiles to batter in thick walls. So, funny little pipelike objects appeared. They made a terrifying noise and their own artillerymen were afraid of them, for they often back-fired. About the only mark they could hit was the broadside of a medieval château. But against these hitherto impregnable battlements they were effective. They brought a new era—an era of kings imposing obedience on robber barons and merchants plying a profitable trade in primitive cannon.

It was inevitable that the manufacturers of armour and swords should enter this business. Just as, a few years ago, livery-stable proprietors set up as garage keepers and coachmen suddenly became chauffeurs, so did the armourers of the Middle Ages adjust their tools to the making of guns and mortars. All through the Black Forest, down in Bohemia at Prague, up the Rhine at Solingen which is now the centre of cutlery manufacture, forges that had previously turned out doublets, corselets, helmets and jousting lances now produced guns. In Italy, at Brescia, Turin, Florence, Pistoia, and Milan, new arms were born from the fertile minds and agile fingers of expert craftsmen. In Spain, in Toledo and Seville, Moorish artisans shaped their famous swords—for not until the twentieth century was the sword relegated to parades and museums—and tried their skill at new weapons. But the most active centre of gun-making was in Belgium.

The country thereabouts had all the elements of nature necessary for this industry. There was plenty of iron and coal, and the rivers and roads offered excellent transportation facilities. On both sides Germany and France wasted their resources in long and costly wars, while Liége, comparatively tranquil, waxed prosperous. The Liégeois were endowed with high inventive and commercial talents and they were admirably fitted to exploit their strategic position. Black Forest forgemen might make guns for their own rulers, but Liége sold to all the western world.

But as decades went by, the sale of arms to other countries from Liége developed so fast that Charles the Bold of Burgundy issued an edict forbidding the Liégeois to manufacture arms. The burghers defied Charles and he proceeded to enforce the measure by besieging the city. His banners and bombarding cannon were successful; Liége was captured and burned, and those of its inhabitants who did not escape were slaughtered. But the arms industry has a tenacious quality undreamed of in the plans of dukes, and hardly was Charles in his grave than the plucky Liégeois were back again at their forges.

In 1576 they were responsible for a most singular transaction. In that year the Duke of Alva brought his Spanish legions to the Low Countries. He slaughtered Protestants, and Catholics too, if they displayed a tendency to act like patriotic Netherlanders. But his arms were not all made in the furnaces of Toledo or Seville. The arms makers of Liége sold him some of the guns, cannon and ammunition with which he fought their compatriots. This is the first recorded instance of the international—the anti-national—traffic in arms.1

Other lords besides Charles the Bold sought to curb these unscrupulous merchants. The Germans, having a vague feudal claim to the Low Countries, reminded the guilds of Liége that they were part of the duchy of Westphalia and for this reason could not legally sell arms and ammunition to the enemies of the Germans. But, like the true prototypes of Vickers and Schneider that they were, they ignored this edict. Later, when all this territory was conquered by France, they were forced to obey similar orders from French republicans and from Napoleon I. But despite this, their industry flourished. By the middle of the eighteenth century, Liége was producing about 100,000 pieces a year and was well known as one of the arms centres of Europe.

From the very first the arms industry had to struggle against more potent adversaries than chance rulers like Charles the Bold or the German dukes. Generals did not die in bed in olden times; they wielded their swords gallantly in the melee of battle and took their chance amid the massed ranks of pikemen and cavalry. The ruling military caste of early modern times scorned these cowardly devices for killing at a distance, and guns, save for besieging purposes, were held in low esteem. Indeed, the European upper classes were very similar to the Japanese Samurai in their resistance to change. When Dutch traders came to Japan in the sixteenth century they found plenty of gunpowder but strong objections to using it in combat. According to the doctrines of the Bushido (Way of the Warrior) it was dishonourable to meet one’s enemy except with cold steel face to face. The European Bushido held the arms industry back for centuries.

Only in the chase was the new method of killing considered proper. So fond did the nobles become of their first crude fowling pieces that they forbade any person not of noble birth to hunt with them. The arms makers of Liége and other cities found much profit in this early sporting goods industry—and more than profit, for as they brought in innovations and proved their worth in the field or covert, the nobles perceived the value of new inventions, and, however grudgingly, accepted them in their ordnance departments.

There were other obstacles to rapid evolution. Science was crude and slow in those heavy-footed centuries, and so it took hundreds of years to better the new instruments of war. It is indeed a far cry from the crude Liége “ bombardes ” to the finished product of Vickers and Schneider; and from the unwieldy arquebuse to the slim Winchester. In the case of artillery the first cannon were of ridiculously small calibre; the little pieces consisted of bands of iron held together by strips of leather. Naturally large charges of gunpowder were dangerous. Likewise small arms were really large arms, for musketeers had to rest their cumbrous arquebuses on forked rods to aim them and an assistant had to stand by with a fuse.

The problem of igniting the powder charge presented the chief difficulty to small arms inventors and merchants. From the time when Columbus discovered America up to the Napoleonic wars, progress in perfecting the lock, the trigger and the firing breech was extremely slow. Decades rolled by before the arquebuse with its portable fuse evolved into the crude match-lock in which the fuse was attached to the breech. Then a century more to develop the wheel-lock, a spring contrivance, not much better, but requiring the use of a trigger. In the seventeenth century some unknown worker hit upon the use of flint struck by steel, and so the flint-lock musket, the weapon of the soldiers of Marlborough, Frederick the Great and Washington, was invented. These flint-locks missed fire often, and when it rained the slugs of powder and ball, loosely packed in paper and rammed down the muzzle, were generally useless. And the barrels, unrifled and short in length, were incapable of accurate aim; only in masses of infantry were they at all effective. Early modern times were indeed the infancy of the arms industry.

In a purely commercial sense, the arms makers were awakened by the French Revolution. The execution of Louis XVI brought all Europe together in league for the extinction of the French peril. England swept the seas of French commerce; Germany was both ally and host to the embittered French émigrés; the Emperor of Austria, mourning his lost relative Marie Antoinette, mobilised his legions at various points—on the Rhine, in Italy, and most important of all in Flanders. Thus the arms merchants of Liége were prevented from plying their usual trade. The British blockade kept American arms shipments from arriving in French ports, and it looked as if the revolutionary government of France would have to depend on their own poorly organised arsenals. However, there was one possible channel for importations.

Would the arms makers of Germany and Austria stifle their patriotism and sell to the French enemy, and if so, would the neutral Swiss cantons let the stuff go through ? That was the problem, and the desperate Committee of Public Safety sent Citizen Tel and Citizen Chose to Geneva, to Basle, to Zurich and even to Germany and Austria, to sound out the armourers. Soon reports like the following came in to the Committee from their agents: “ The landgrave of Hesse, avid for money, is ready to serve whoever will pay him the best.” Cupidity triumphed, and it was the old story of the Liégeois and the Duke of Alva.

As for the neutral cantons, they were handled satisfactorily. The sellers packed their goods in the most innocent and disarming of crates so that they looked like anything but shipments of arms, and the carriers had orders to take them by certain sure and devious routes. One shipment from Germany totalled 40,000 muskets, and soon caravans of copper, that necessary metal in making shells, came all the way from Austria itself. The Swiss government assured the Emperor that they were permitting no such breach of neutrality, but the two streams flowed on—the agents equipped with fat letters of credit into Central Europe, and, in the other direction, the masked wagon-loads of arms. It was a curious parade, but as will be seen in a later and more important war, it was not to be the only one of such a nature to pass through Switzerland.

It was most effective, and while the reorganisation of domestic firearms industry was perhaps a larger factor in the supply of the French armies, yet this foreign aid from German and Austrian sources made success more certain. Valmy, Wattignies and the victories in Flanders sent the armies of the Coalition back to their bases and saved the French revolutionary government. French arsenals were now competent to equip the armies, and the French generals turned from the defensive tactics of Danton and the Committee of Public Safety to carrying the war into the enemy’s camp under the Directory and Napoleon. But even the latter did not scorn aid from foreign makers of lethal weapons.2

In 1797 Robert Fulton was in Paris. He had not yet drawn the plans for his famous steamboat, but he had invented another watercraft to exploit which he formed a company. It was the first submarine, and when the Fulton Nautilus Company submitted proposals to the French government, there was much excitement in French naval circles. Old line admirals, like chivalrous knights in armour, considered the invention cowardly and unworthy of French martial honour. However, members of the Directory and scientists employed by Napoleon, who soon after seized the power from the Directory, were inclined to favour it.

Limited funds were advanced to Fulton and trials took place. The Nautilus was a crude apparatus, submerging by admitting water to the hold and rising by pumping it out, but the tests were quite successful. At one time a contract was drawn up, which curiously enough had a most patriotic clause inserted at the request of the inventor, providing that the Nautilus should not be used against the United States unless the latter used it first against France. But in the end French naval conservatism and red tape triumphed. Fulton’s proposals were rejected and he went to France’s adversary, England, to market his product. He found the English admirals just as conservative and contemptuous of his craft, and after discouraging negotiations he abandoned the enterprise and set sail for New York.3

Fulton’s ship was hardly out of sight of Land’s End when another inventor knocked on the door of English conservatism. Up in Scotland a Scots minister named Alexander Forsyth liked fowling but found his flint-lock gun a most unsatisfactory affair. On his shooting expeditions across the moors he was enraged when the powder and ball often failed to explode just after he had taken aim at a fat grouse. He had a turn for tinkering with mechanical contrivances, and he began to experiment with methods of ignition. The result was a form of the percussion cap, inserted in a pan on the breech of the gun. It was crude, but it was at least successful in withstanding the damp mists of the Scottish highlands.

Forsyth saw commercial possibilities in it and went to London to get a patent. There he met Lord Moira, head of the government ordnance works. Moira was enthusiastic about the invention, encouraged Forsyth to perfect it, and gave him a room in the Tower of London as a workshop. Preaching in a neighbouring chapel on Sundays and bent over his bench in the Tower during the week, the clergyman worked out some excellent improvements on the cap. But, alas, Moira resigned, and his successor, Lord Chatham, a believer in the status quo in arms, saw nothing but idle foolishness in Forsyth’s work. He dismissed him and ordered him to take his “ rubbish ” out of the Tower.

Poor Forsyth, a victim of military obscurantism, retired with his caps and apparatus. But not before Napoleon offered him £20,000 for the invention. As in the case of Fulton, patriotism meant something to the minister. Rather than give old Bony, “ the mad dog of Europe,” a chance to win battles by it, he refused and retired to his kirk. Twenty years later the percussion cap was accepted by the British government, and a pension was granted Forsyth. But it came too late; the first instalment arrived the morning of his death.4

Thus in the case of this Scottish clergyman the various obstacles which faced arms merchants and inventors at the close of the eighteenth century were all present. They had to demonstrate the effectiveness of their products in such inglorious ways as hunting before they could attract the notice of ordnance ministers. Then they had to overcome the rigid conservatism of the military, just as resistant to change on the score of tradition and honour in arms as a Japanese Shogun. And lastly, patriotism often restrained them from the full exploitation of their merchandise.

But by this time the industrial revolution was in full swing, capitalism was invoking new standards. Fulton and Forsyth, after all, were inventors rather than arms merchants. Would the large companies which were now growing powerful still adhere to the old code of national honour ? Was patriotism strong enough to resist a new code of business ?

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 Revue Economique Internationale, 3 (3) Sept. 1929, pp. 471-492. Albion: Introduction to Military History, pp. 5-44.

2 Camille Richard, Le Comité de Salut Public et les Fabrications de Guerre sous la Terreur; Charles Poisson, Les Fournisseurs aux Armées sous la Revolution Française: le Directoire des Achats (1792-1793).

3 H.W. Dickinson: Robert Fulton, pp. 65-206.

4 Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. 7, p. 471.

ABOUT the time when Robert Fulton was cooling his heels in Napoleonic anterooms, a young man named Eleuthère Irénée Du Pont journeyed to America.1 He was the son of a famous French radical intellectual who, like so many of his class, had long entertained a romantic love for the new republic across the Atlantic. Reports of its constitution and its founders corresponded with all the ideas of the current French writers who inspired the younger generation in France to revolt against the monarchy.

He was an intellectual, but not without an eye for commercial prospects. He saw more in America than a laboratory of political science. His father, Pierre Du Pont, had invested heavily in a Virginian land company, and his brother Victor was engaged in trade with the West Indies out of New York. Accordingly, in a rich land like America it was not long before he saw a chance to invest his own not inconsiderable patrimony.

One day he went hunting with a French veteran of Washington’s army. So abundant was the shooting that he had to lay in an extra supply of powder. What he got and the price he had to pay opened his eyes. He received a very inferior grade of powder at an exceptionally high price. Now thoroughly interested, he visited powder mills, studied prices and came to the conclusion that America was a good country in which to start a powder business.

Indeed, he had some experience in this line. He had an excellent scientific education and had specialised in chemistry at Essonne. One of his father’s best friends was Lavoisier, the greatest chemist of the time in France and the supervisor of gunpowder manufacture for the French government before the revolution. And Lavoisier had helped the son of his friend in his studies.

After making estimates of the cost of building a mill and purchasing supplies, Irénée returned to France to get material and financial backing. He was aided by the political situation in Europe. Napoleon was letting no opportunity pass which promised to harm his most formidable enemy, England. If young Du Pont could set going a successful powder mill in the States, England, which sold most of this product not only to America but to all the world, would be affected. Therefore the First Consul gave orders that all possible aid be given to Du Pont. So government draftsmen made plans and government arsenals manufactured machines for the new enterprise. And plentiful capital was forthcoming. The affair started under favourable auspices.

Thus in 1802 there came into being the first great American powder factory under the name of Du Pont de Nemours, Père et Fils et Cie; later Irénée, the moving spirit, changed it to his own name—E.I. Du Pont de Nemours and Company; but it was sufficiently French to attract the Francophile spirit which was prevalent in America at that time. The new company prospered from the beginning. In four years the mills turned out 600,000 pounds of powder. Irénée’s calculations had proved correct. He had seen as well as Napoleon that American manufacturing could cramp English trade, and that this applied especially to powder. He had acted patriotically both for the country of his adoption and for his recent patrie, the enemy of England.

Also he knew the right people in America from the first. In France he and his father had been prominent in the philosophical and radical circles which prepared the way for the French Revolution. They belonged to the right wing of this group, and they barely saved their necks from the guillotine when the extremists prevailed. In the earlier days of the Revolution old Pierre was at different times both President and Secretary of the Constituent Assembly and voted against the execution of Louis XVI. Naturally after this he was out of favour with the Jacobins. Pierre retired from politics and spent his time editing the works of his master Turgot. This impeccable record as moderate radicals was a strong recommendation to the powerful group of philosophic politicians in America who sympathised with them.

Prominent among these early friends in America was Thomas Jefferson. Irénée counted on the aid of the President, and Jefferson did not fail him. The President wrote to the young powder merchant:

“ It is with great pleasure I inform you that it is concluded to be for the public interest to apply to your establishment for whatever can be had from that for the use either of the naval or military department. The present is for your private information; you will know it officially by application from those departments whenever their wants may call for them. Accept my friendly salutations and assurances of esteem and respect.

“ (Signed) THOMAS JEFFERSON.”

In other words, Du Pont had inside influence. Orders came in as promised, and they were so satisfactorily filled that Jefferson wrote another letter to Du Pont praising the excellence of the product, which he himself had tested on a recent hunting expedition. But the orders did not come in as large quantities as expected. Perhaps it was youthful impatience, but Du Pont was not satisfied. While Jefferson had interceded in his behalf, the Secretaries of the Army and Navy had the ordering of war supplies. Although Secretary Dearborn declared that the Du Pont powder was the best, orders up to 1809 amounted to only $30,000. It seemed that Dearborn was not sufficiently impressed with the need for preparedness in peace times.

But after 1809 there was a change. British men-of-war had begun the irritating practice of “ impressing ” American seamen, and relations between Britain and America became embittered. War was in the offing, and in 1810 orders for powder doubled and trebled. When the War of 1812 did break out, Du Pont sold virtually all the powder the country required. Records of the company tell how the little factory at Wilmington rushed several hundred barrels of powder to Washington when that city was attacked by the British troops. Government connections, Du Pont—as well as many other war dealers—found, were very profitable.

But, like others of his craft, Du Pont also found that post-war years are the hardest. Orders declined, there were great surplus stocks, and he had spent money expanding his plant. Yet when the government wished to dispose of large quantities of damaged powder, Du Pont generously took it off their hands at a low price. On top of that there was a terrific explosion which practically destroyed the whole establishment. Patriotism, he found, was an expensive sentiment.

Yet he resolved to make his company entirely American—a difficult task in his situation, for capital was scarce in the new country. But he returned to France and found that his renown had spread to such an extent that soliciting funds was not an insuperable task. Many famous and wealthy people, among them Madame de Staël and Talleyrand, contributed to his financing. But however grateful he was, Du Pont felt that this was foreign gold, to be employed only in an emergency. He would work hard and pay it off as soon as possible. He returned to America with new vigour. He rebuilt his plant and made it more efficient than ever. Now he sold his product to whoever wanted it—to Spain, to the West Indies and especially to the South American republics which were in ferment of revolution against Spain. It will be noticed that he was not averse, however much he sympathised with the partisans of Bolivar, to selling to both sides in these wars. This sort of transaction required credits, and he could obtain only short-term financing in America at that time. In one of his letters he complains about the strenuous rides he had to make once a week to the banking centre some sixty miles away, to take up his notes.

All the more reason then that he should be tempted to fill an order that came to him in 1833. All through 1832 the State of South Carolina had seethed with rebellious talk. Among the hot-blooded planters there were sprouting the seeds of the spirit which later produced Sumter and the Confederacy; for import duties, imposed at the suggestion of Northern manufacturers, had roused a tempest, and for the first time since the founding of the Union there was serious talk of secession.

So serious was it that among the more daring Carolina leaders there were some who laid plans for armed defence. They gave an order to one of Du Pont’s agents for a shipment of 125,000 pounds of powder, and they offered, which was most unusual among Du Pont’s credit-seeking clients, $24,000 in cash. Here was an excellent opportunity to clear off his foreign debts, but the integrity fostered by his radical education, together with his early love for the Union, triumphed. However much he wished to become wholly American by the erasure of his obligations, he felt that he could not achieve this independence by descending to such commercial methods. He wrote to his agent: “ The destination of this powder being obvious, we think it right to decline furnishing any part of the above order. Whenever our friends in the South will want sporting powder for peaceful purposes we will be happy to serve them.”

But he felt that his civic duties were not entirely satisfied by this refusal. He was now a public figure in government councils, a director of the Bank of the United States and a member of various organisations devoted to the economic welfare of the country. He hurried to Washington to see if he could assist in patching up a truce between the Northern industrialists and the fiery planters. After protracted negotiations a compromise was reached and the affair subsided. Indeed, the storm was succeeded by such a friendly calm that he could not help writing to his Southern agent in a jocular mood: “ Now that the affair has ended so amiably I almost regret that we refused to supply the powder. We would be very glad to have that $24,000 in our cash, rather than that of your army.”

A few years later Irénée died, after seeing his dream come true through the payment of his foreign debt and the completion of his plans for a 100 per cent. American firm. His successor, Alfred, was a little more aggressive. Vigilant for his country’s defence, he observed that “ our political dissensions are such that it would require the enemy at our doors to induce us to make proper preparation for defence.” Such talk of “ preparedness ” is not unusual among arms manufacturers. Also the words “ government ownership ” came to plague this early war dealer, and, commenting on a Presidential message in 1837 which recommended construction of a government powder plant, he objected on the ground that it would cost the government much money without corresponding savings.

But a real test of his sincerity came in 1846—a test that was far more difficult than the one Irénée faced in 1833. Two imperialisms had clashed on the Rio Grande, and war was declared between Mexico and the United States. At the outset there was the usual slogan, “ Stand by the President,” raised. But James K. Polk was one of the least ingratiating persons who had ever sat in the Presidential chair. Also he was a Southerner, and it was not unnatural that Northerners should assert that the war was simply a Southern plot to bring more slave states into the Union.

James Russell Lowell began it with his jingles in the Biglow Papers—

They jest want this CalifornyDaniel Webster flung his oratory into caustic criticism of the war, and he was abetted by fanatics like Sumner. Soon, drinking of this heady fire water, Northern newspapers were fulminating against Polk and the continuance of the war. This was one of the few wars waged by the United States in which the enemy was popular. Black Tom Corwin said that American soldiers in Mexico should be welcomed by “ hospitable graves,” and a whole nightmare school of literature sprang up. Some papers called for European intervention. One said editorially: “ If there is in the United States a heart worthy of American liberty, its impulse is to join the Mexicans.” Another said: “ It would be a sad and woeful joy, but a joy nevertheless, to hear that the hordes of Scott and Taylor were every man of them swept into the next world.” Santa Anna, the rascally Mexican commander, became a hero in Boston and New York, and there was even a contingent of Americans who fought with the Mexican army.2

With this background, Du Pont, a strong Whig and anti-slavery partisan, could hardly feel much enthusiasm for the war, even if it did bring him government orders for powder. A few weeks after the declaration of war a strange order came to him from Havana for 200,000 pounds of powder. It was obviously from a Mexican source, and thus a fine opportunity was offered the powder-maker to aid “ poor Mexico ” and deal a blow to the slavery plot which he hated so much. But with abolitionist journals attacking the American “ persecution ” and prominent men everywhere urging non-co-operation and even helping the enemy, Du Pont flatly refused to fill the order.

The tempters returned a second time, more cleverly concealed. A Spaniard and a Frenchman placed an order with the Du Pont company for the same amount. They asserted that it was not destined for Mexico and went to the trouble of supplying references from two American firms. But Du Pont investigated, and came to the conclusion that it was another masked Mexican requisition. “ However unjust our proceedings may be, and however shameful our invasion of Mexican territory, we cannot make powder to be used against our own country.”

The gods of patriotism rewarded Du Pont after the war was over by withholding from him the usual plague of post-war depression which perennially visits arms manufacturers; for the West was expanding. In Ohio and Indiana farmers were industriously clearing away timber land, and potent charges of Du Pont powder were needed to extract the stumps. This was the first era of railway building, and powder was a necessity for railroad contractors. William Astor and his Oregon Fur Company needed powder for hunting in the Northwest. Mining was also beginning to develop.

Du Pont did not need a war, but the gods smiled and gave him one. In 1854 England, France, Turkey, and others went to war with Russia, and guns in the Crimea required powder. England had exhausted her own supply and she turned to Du Pont, while Russia also sent orders to Wilmington. Du Pont filled them both. After all, he, like other Americans of the time, felt no particular sentiment for either side in that remote struggle. From the homespun little factory on the Brandywine, shipments of the “ black death ” went forth to the far corners of the globe.

In these days before the Civil War, only a few rough buildings comprised the workshops, laboratory and drying-houses. Several hundred descendants of French Revolutionary soldiers served as employees, like serfs for a medieval baronial family, and the president had his office in a mere shack on the grounds, for the Du Ponts had the ingrained French spirit of conservatism. The elder Du Pont refused to employ a secretary—a far cry from the present, when secretaries to the secretary are the order of the day. Clinging to old traditions, he refused to send his product by railway, and long mule teams made deliveries even to great distances.

Du Pont, like the military traditionalists of England and Prussia of that day, turned down guncotton, which later he was forced to use. Indeed, there was not much reason why he should yield to these new things, for his natural conservatism was aided by his dominating position in the backward economic system of the time. Governments had to come to him with orders, and it was a matter of indifference to him whether he sold war material or not. Competition in the powder business was not keen. Besides, the winning of the West required so much hunting and blasting powder that he did not care whether cannon fired or not.

During the American Civil War Du Pont was again the patriot—at least the Northern patriot. Two days after the fall of Fort Sumter, when Secessionists were offering huge sums to war dealers for supplies, Du Pont wrote to his Richmond agent: “ With regard to Col. Dimmock’s order we would remark that since the inauguration of war at Charleston, the posture of national affairs is critical and a new state of affairs has risen. Presuming that Virginia will do her whole duty in this great emergency and will be loyal to the Union we shall prepare the powder, but with the understanding that should general expectation be disappointed, and Virginia by any misfortune assume an attitude hostile to the United States, we shall be absolved from any obligation to furnish the order.” Naturally, the war brought Du Pont large orders, and he was the mainstay of the Northern government.

The Civil War had created a virtual partnership between Du Pont and the government. When the war was over this relationship was not disturbed. In close co-operation with the government Du Pont now began experiments in new powders. In 1873 he patented a new hexagonal powder, together with a machine to compress it. The government tested it and found it a success. The British heard of it and at once placed an order for 2,000 pounds of the powder. It was filled at once, possibly with the hope of securing further British orders, for Du Pont surmised that the British proposed to compare it with “ an analogous powder ” for which it paid an English manufacturer nine cents a pound more than the Du Pont price.

In 1889 the government made use of Du Pont in securing certain superior European gunpowders. The brown prismatic and smokeless powders of the Belgians and the Germans were reputed to be better than the American product. Under government urging Alfred Du Pont went abroad to buy the rights to manufacture these powders in America, and Eugene Du Pont went to Europe to learn the methods of manufacture. Working hand in glove with the government became a regular practice with Du Pont. In 1899 a smokeless powder plant was erected by the government at Indian Head, and, according to a Congressman, “ the Du Pont Company assisted the officers of the United States in every possible way... doing everything possible to make the venture a success.” A little later, Congress appropriated $167,000 to build a powder plant at Dover, N.J. According to the same Congressman, “ the Du Pont Company not only gave the government officials free access to all its plants, but turned over their blueprints to them, so that when the factory was complete it represented every modern feature.”3

A curious problem arose in 1896. Somehow there had grown up a reluctance to kill and blast with black or brown powder. Du Pont acceded to the demands of his customers by manufacturing smokeless powders in thirteen different colours. Here is a letter sent out in regard to the matter:

“ We can dye the powder almost any colour desired. We send you a box of thirteen smokeless powders—all of these are on the market and you can judge of the colours.... We also send you some small bottles of Du Pont powder dyed various colours. Some are very pretty. If you do not like any of them we can send others, as we have a multitude of shades.”

The last decades of the nineteenth century witnessed the formation of powerful combines and trusts in American business. It was only natural that Du Pont should be transformed from a simple powder company into a gigantic combine with international ramifications. This development came as a result of the Civil War. Government orders had been so reckless that the supply of powder on the market proved a drug to the entire industry. The government sold its surplus at auction prices and the bottom fell out of the powder industry. But complaining did not help. Something must be done.

And something was done. Beginning in 1872 the Du Pont Company gradually brought “ order ” into the industry, and in 1907 it was not only supreme in the field, but had virtually united all powder companies in the country under its guidance, control, or ownership. It is a long story which has been told in detail by William S. Stevens in The Powder Trust, 1872-1912.4

It began with a series of price-fixing arrangements. The industry was in a state of chaos. A keg of rifle powder which ordinarily sold for $6.25 brought only $2.25. The Gunpowder Trade Association of the United States was formed in 1872 by seven of the largest companies, and immediately a minimum price was fixed for powder. Independents who would not enter the association were forced to the wall by systematic underselling. Others were brought into line by purchase of so much of their stock that they could be controlled.

The situation seemed well in hand when another threat menaced the industry. The Europeans decided to enter the American field by erecting a factory at Jamesburg, N.J. The companies concerned were chiefly the Vereinigte Köln-Rottweiler Pulverfabriken of Cologne and the Nobel Dynamite Trust Company (Ltd.) of London. This menace was met in characteristic fashion. In 1897 an agreement was signed by the two groups, the European and the American, three points of which are of interest here as an example of co-operation between armament manufacturers:

1. Neither group was to erect factories in the other’s territory;

2. If any government sought bids from a foreign powder manufacturer, the foreigner was obligated to ascertain the price quoted by the home factory and he dare not underbid that price;

3. For the sale of high explosives the world was divided into four sales territories. The United States and its possessions, Central America, Colombia, and Venezuela were exclusive fields of the American powdermakers; the rest of the world (outside of the Americas) was European stamping ground. Certain areas were to be open for free competition.

With the European menace thus removed, Du Pont now sought full control of the American field. The policy pursued was one of ruthless elimination. From 1903 to 1907, one hundred competitors were bought out and sixty-four of these were immediately discontinued. This narrowed the field very considerably, leaving only such companies as were either affiliates or allies. How ruthless this process of elimination was may be seen from the description of one who was in a position to know, Hiram Maxim. He writes: “ The Phoenix Company undertook to buck the Du Ponts in the powder business. They were just about as wise as the little bull who bucked a locomotive—there was no more left of the Phoenix Company than there was of the little bull.5

The result of this monopolistic policy may be seen in the fact that by 1905 Du Pont controlled the orders for all government ordnance powder. Having established this monopoly, Du Pont turned again to pricefixing. Hitherto prices had been quoted locally or regionally. They were one thing in the East, another in the West, still another in the South. Now, however, national prices were established from which there was no deviation.

About this time Du Pont encountered another obstacle. The Federal government had passed the Sherman anti-trust laws in 1890, and in 1907 it finally got round to taking a look into the activities of the Du Pont Company. It brought an action against the company in 1907, charging it with a violation of the Sherman Law. But the government was in a quandary. It proposed to restore conditions to what they had been before Du Pont began its monopolistic activities. Du Pont, however, had wiped out most of its competitors by purchase, so that it was impossible to restore the status quo ante. The government did manage to set up two great independent companies as a result of its suit.

During the World War, Du Pont supplied 40 per cent. of the powder used by the Allies, and after 1917 its orders from the United States government were enormous.6 To-day the Du Pont Company owns and operates more than sixty plants in twenty-two states of the Union. Five research laboratories and more than eight hundred and fifty chemists and engineers have taken the place of the individual inventor. Every year it grants twenty research fellowships. It manufactures a multitude of products, including chemicals, paints, varnishes, rubber goods, cellophane, rayon, and countless others, but it is still the largest and most important powder-maker in the United States.7 Yet it is rather significant that, according to its own figures, only 2 per cent. of its total manufactures are in military products.8

Locally the Du Pont Company is very powerful. It “ owns ” the state of Delaware; and the city of Wilmington, with its various Du Pont enterprises, hospitals, foundations, and welfare institutions, everywhere recalls the powder-maker dynasty. The three daily newspapers of Delaware are all controlled by Du Pont.9

This local control, like that of a great feudal lord over his fief, has by and large satisfied the Du Ponts. They have never sought prominence in national politics, though members of the family have—almost by accident—become United States Senators. Their relationship with the government has always been very close, and this has been due just as much to the government as to the Du Ponts. In their early period the demand for hunting and blasting powder was so active, and later their enterprises were so diversified, that they did not need wars to insure prosperity. But whenever the government required its aid, in peace and in war, the company was ready to co-operate—usually with neat profits for itself.

Du Pont could afford to cling to his ideals; he could indulge in the sometimes expensive sentiment of patriotism, so well was he entrenched. But there were other merchants, less secure and less scrupulous.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 The Du Pont story is told in B.G. Du Pont, E.I. Du Pont de Nemours & Company, A History, 1802-1902. (New York, 1920); Anonymous, The History of the E.I. Du Pont de Nemours Powder Company. (Business America, 1912.)

2 Justin Smith, Way with Mexico, Vol. II, pp. 68-84.

3 Anonymous, The History of the E.I. Du Pont de Nemours Powder Company, p. 76s.

4 Ph.D. thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 1912. See also Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1912, for summary.

5 Clifton Johnson, The Rise of an American Inventor, p. 185.

6 “ Du Pont de Nemours Powder Company, E.I.” Encyclopaedia Britannica (14th ed.).

7 “ Research,” Encyclopaedia Britannica (14th ed.).

8 Stockholders’ Bulletin, June 15, 1933.

9 Arthur Warner, Delaware. The Ward of a Feudal Family [in Gruening (ed.), These United States].

AMERICA made excellent gunpowder. It also produced superior small arms. The end of the Civil War gave a tremendous impetus to the sales campaign of American arms manufacturers. The bottom had more than fallen out of their domestic market. With large plant, personnel, and stocks on their hands, the arms manufacturers had to seek foreign outlets. Moreover, the second-hand merchants were pressing them in the smaller countries, and they found it necessary to seek out the ordnance departments of the Great Powers. But the most potent cause for expansion was that the world was ready to buy American small arms.

A trio of American manufacturers had emerged whose products were now world famous—Colt, Winchester, and Remington. As early as 1851, at the London World’s Fair, American rifles were a sensation, and they received medals. The British sent commissions to the United States to study factory methods, and they were gladly and proudly shown through various arsenals. This hospitality had its reward in immediate and large orders. Between 1855 and 1870 the following governments bought American machinery for the manufacture of rifles and pistols: England, Russia, Prussia, Spain, Turkey, Sweden, Denmark, and Egypt, to mention the most important. Others followed in subsequent years—namely, Japan, Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Mexico.

So important did this branch of American industry become that the United States government issued a special Report on the Manufacture of Fire-arms and Ammunition, prepared by Charles H. Fitch, giving detailed descriptions with drawings of American machinery for the manufacture of small arms.1 The Report records that there were then thirty-eight establishments in the United States making small arms and five establishments manufacturing ammunition for these.

There was a reason for this. Back in the early years of the century, Eli Whitney, the inventor of the cotton gin, turned his attention to rifles. He told Jefferson that he could make rifles so much alike that any part of one would fit another. Army officers ridiculed the idea, but Whitney went ahead and set up a shop which demonstrated the practical value of interchangeable parts. Whitney’s muskets were used in the War of 1812 and scored a great victory for this kind of manufacture. Whitney’s principle was adopted by all of modern industry and made possible the era of mass production.2

Samuel Colt was one of the first to develop Whitney’s ideas.3 He was enchanted by the idea of the arms merchants’ business from his early youth. He had been absorbed by the story of Fulton’s attempt to sell a submarine and torpedo to the French and English governments, and he had an aptitude for inventing. He perfected a torpedo which amazed President Tyler, but it did not impress the military traditionalists of the War Department, who took no steps to aid in its development. Indeed, some of Colt’s early struggles bear a certain resemblance to Fulton’s.

However, it was not a torpedo upon which he based his hopes. It was the first revolver of modern times. There were many four-barrelled pistols made before the nineteenth century, but they had all been handicapped by unsatisfactory firing devices and general clumsiness of construction. But at the time Colt began tinkering with pistols, the percussion cap was in use. Colt took out a patent on his first revolver in 1835. He established a factory in Paterson, N.J., capitalised at $250,000, and submitted his product to the War Department.

Trial was made before a committee of officers, who reported unanimously that they were “ entirely unsuited to general purposes of the service.” But Colt would not be discouraged by the obtuseness of these conservatives. He made further improvements in the weapon and took it himself to Florida, where the United States was waging a form of Guerilla warfare with the Seminole Indians. There he interested many army officers, who reported favourably on it, but not strongly enough to make the War Department reverse its decision.

Colt’s company failed in 1842, a victim of military conservatism, but meanwhile, unknown to the executives, the revolver was making a great success in Texas. Fighting conditions there required some improvement on the slow-firing muskets in use at that time. It was horseback fighting with stealthy Indians and Mexicans who could use the lariat, and a weapon was needed which could be fired rapidly from the saddle. Colonel Walker and other dare-devils who made up the famous Texas Rangers found the new revolver a priceless and indispensable arm in this sort of warfare. Indeed, the history of the conquest of the great plains was largely the history of the Colt revolver. These weapons in the early ’forties sold for as much as $200 apiece, which must have given the bankrupt Colt ample cause for thought when he recollected that he had offered them to the War Department for $25.

The Mexican War brought a reversal of Colt’s misfortune. General Zachary Taylor found that his scouts who were Texas Rangers were invaluable, and that one of the reasons was their use of the revolver. Accordingly, he sent imperious demands to the War Department for large orders of Colts. The War Department gave Colt an order for 1,000 revolvers at a price of $24,000, and the inventor immediately started another factory in Connecticut to fill the order. It is said that he had great difficulty in obtaining in the East a sample revolver to serve as a model for his workmen, so much in demand were they in the South-west. From this time on Colt’s fortune was made.

He adopted Whitney’s system of accurate manufacture, by machinery, of revolvers and carbines; and all his products were neatly and uniformly made. The great virtue of his process was that parts were interchangeable—a virtue that hand-made pistols and rifles lacked. Soon he had a fine business, sending shipments of triggers, sights, barrels, mainsprings, etc., to all parts of the country where revolver users wished to repair their weapons. That this was a revolutionary procedure, virtually unknown in Europe, may be noted in the minutes of the British commission to investigate the conditions of small arms manufacture. Colt, who had established a factory in London, made a great impression on his English interlocutors by his positive opinions on the superiority of his process of manufacture. The following is testimony to the condition of the small arms situation in Europe at that time:

INVESTIGATOR: Do you consider that you make your pistols better by machinery than by hand labour ?

COL. COLT: Most certainly.

INVESTIGATOR: And cheaper, also ?

COL. COLT: Much cheaper.

Colt became immensely wealthy, and a large part of his business came from abroad. He sold to the Czar of Russia, particularly, and his products were in use during the Crimean War, on both sides. His home in Connecticut, well named Armsmear, was filled with jewelled snuff-boxes, diamonds, testimonial plates and other gifts from such monarchs and leaders as the Czar of Russia, the Sultan of Turkey, the King of Siam, Garibaldi, and Louis Kossuth.

The Winchester rifle also benefitted by American efficiency processes. It was much in demand, and Winchester was noted particularly for his far-travelling and aggressive salesmen. The Winchester repeating rifle, a new marvel in the ’sixties, became so famous that the Arab tribes of Africa later demanded Winchesters even from their second-hand dealers. When Winchesters were not available in sufficient numbers, the merchants of used guns at times forged the Winchester label on the gun and thus satisfied their customers.

The Winchester can tell of other triumphs. In the 1860’s Mexico became the stage of French imperialist ambitions. Napoleon III placed Maximilian and his devoted queen Carlotta on the Mexican throne, but the Mexicans resented the foreign invasion and refused to recognise their new monarch.

Among the leaders of the rebellion was Don Benito Juarez, former President of Mexico. Juarez had heard of the wonderful repeating rifles of Winchester and immediately placed an order for these new products of Yankee ingenuity. The Winchester Repeating Arms Company was ready enough to fill the order, but it wanted to be sure of its money before making delivery.4

“ Colonel ” Tom Addis, world salesman extraordinary, took a shipment of 1,000 rifles and 5,000 rounds of ammunition to Brownsville, Texas, right on the Mexican border. For two months he waited here before Juarez gave orders that the munitions be brought to Monterey. Addis journeyed the 240 miles by ox-cart train, placed his cases in a storeroom and covered them with the American flag. For more than four months Juarez tried to get these arms, promising to pay later; but Addis insisted on cash. Meanwhile Maximilian heard of the Winchesters at Monterey and made frantic efforts to get them for himself. Addis notified the Juarez forces that unless he received payment at once the arms would be sold to Maximilian. Almost immediately keg after keg of loose silver coin arrived and the arms were delivered to Juarez.

Another great problem remained for the doughty Addis: the delivery of his kegs of silver to his company. He loaded his coin into an old stage-coach and headed north for the American border. Hardly out of Monterey he halted the stage-coach, bound his Mexican driver and threw him into the back seat with a noose around his neck. Then he turned out of the highway, where he suspected an ambush, and dashed back to the United States over an old abandoned road. Nine months after leaving the Winchester factory with the munitions, Addis landed his kegs of silver in safety at Brownsville. These Winchesters were one of the factors in the overthrow of Maximilian in Mexico.

The comment of Darlington, who tells this story, is also interesting:

“ This is more than a tale of adventure incurred in the line of duty. It gives some hint of how hardy missionaries of industry were, even so shortly after the Civil War, spreading the gospel of American business into the foreign field.”

In 1816 Eliphalet Remington, a young American frontier lad, begged his father to buy him a rifle. All the other boys had them and he wanted one too. Hunting was good in the neighbouring woods and Eliphalet had ambitions. Remington senior refused his son’s request, and that refusal was to make history.

Young Eliphalet went and made his own gun, took it to a neighbouring town to have it rifled, and discovered that he had an excellent hunting implement. The neighbours discovered this fact also, and before the lad realised it he had become one of the first arms manufacturers in the United States. In this simple and inauspicious manner one of America’s outstanding contributions to the armoury of Mars had its beginning.