Published: October 26, 2010 http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/27/business/27drug.html?_r=3&ref=glaxosmithkline_plc

Cheryl D. Eckard, the company’s quality manager, asserted in her whistle-blower suit that she had warned Glaxo of the problems but the company fired her instead of addressing them. Among the drugs affected were Paxil, an antidepressant; Bactroban, an ointment; Avandia, a troubled diabetes drug; Coreg, a heart drug; and Tagamet, an acid reflux drug. No patients were known to have been sickened, although such cases would be difficult to trace.

In a rising wave, recent lawsuits have asserted that drug makers misled patients and defrauded federal and state governments that, through Medicare and Medicaid, pay for much of health care.

Using claims from industry insiders, federal prosecutors are not only demanding record fines but are hinting at more severe actions.

Suffering a research drought, drug makers have laid off thousands of employees. Some of those dispatched have in turn filed whistle-blower lawsuits that can lead to criminal investigations.

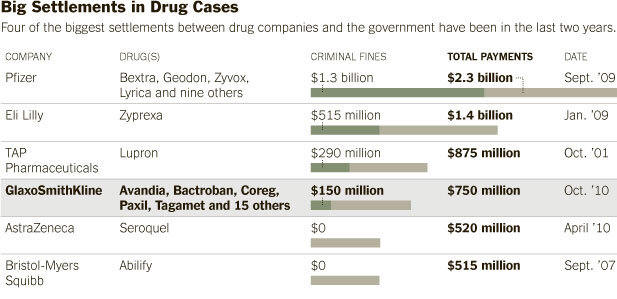

Justice Department officials announced the settlement in a news conference Tuesday afternoon in Boston, saying a $150 million payment to settle criminal charges was the largest such payment ever by a manufacturer of adulterated drugs. The outcome also provides $600 million in civil penalties. The share to the whistle-blower will be $96 million, one of the highest such awards in a health care fraud case.

When asked whether any individual could be charged in addition to the corporation charges, Carmen M. Ortiz, the United States attorney for Massachusetts, would say only that the investigation was not yet complete.

GlaxoSmithKline released a statement saying that it regretted operating the Puerto Rico plant in violation of good manufacturing practices. The company said the problem had involved only one plant that was closed in 2009. American shares in the company fell 0.35 percent on Tuesday.

Tony West, the assistant attorney general in charge of the department’s civil division, said hundreds of such lawsuits were awaiting federal review.

“We’ve opened more investigations, we’ve recovered more taxpayer dollars lost to fraud, we’ve had more convictions, higher penalties and fines in the last two years than we’ve had in any other two-year period,” Mr. West said in an interview.

Whistle-blowers who win earn a cut of the eventual fine. Ms. Eckard will collect $96 million from the federal government, and she will collect additional millions from states.

The suits, all filed under seal, have for years been rising in size and scope, but the collective threat to the industry has been largely unnoticed because the growing mountain is obscured by a wall of judicial secrecy. Each successful claim begets more suits, with more being filed almost every week.

The suits are filed under a federal law originally intended to stop Civil War hucksters from selling rancid meat to the Union Army by paying bounties to tipsters. The pharmaceutical industry has become the law’s most successful target because the government now buys far more pills than bullets, and because fraud in health care is common.

Health care cases accounted for some 80 percent of the $3.1 billion recovered by the Justice Department under the false claims act last year, the Taxpayers Against Fraud Education Fund, a nonprofit whistle-blower advocacy group in Washington, reported on Monday. Most of the money is typically returned to the programs in which false claims were filed, like Medicaid and Medicare.

The Food and Drug Administration and the inspector general of the Health and Human Services Department both announced recently that they would pursue charges against executives personally under a strict liability provision of the law, something that has not been done since 2007 when the three top executives of Purdue Pharma were convicted, sentenced to probation and personally fined $34 million while Purdue paid $600 million.

The rule allows executives to be prosecuted and barred from government sales even if they were not aware of specific violations.

Legislation could make such claims easier to win. Last month, the House of Representatives passed a bill that permits executives to be barred even if they have left the company where the fraud occurred and that permits the inspector general to prosecute parent companies for the sins of subsidiaries.